IT IS a classic startup story, but with a twist. Three 20-somethings launched a firm out of a dorm room at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2016, with the goal of using algorithms to predict the reply to an e-mail. In May they were fundraising for their startup, EasyEmail, when Google held its annual conference for software developers and announced a tool similar to EasyEmail’s. Filip Twarowski, its boss, sees Google’s incursion as “incredible confirmation” they are working on something worthwhile. But he also admits that it came as “a little bit of a shock”. The giant has scared off at least one prospective backer of EasyEmail, because venture capitalists try to dodge spaces where the tech giants might step.

The behemoths’ annual conferences, held to announce new tools, features, and acquisitions, always “send shock waves of fear through entrepreneurs”, says Mike Driscoll, a partner at Data Collective, an investment firm. “Venture capitalists attend to see which of their companies are going to get killed next.” But anxiety about the tech giants on the part of startups and their investors goes much deeper than such events. Venture capitalists, such as Albert Wenger of Union Square Ventures, who was an early investor in Twitter, now talk of a “kill-zone” around the giants. Once a young firm enters, it can be extremely difficult to survive. Tech giants try to squash startups by copying them, or they pay to scoop them up early to eliminate a threat.

-

The campaign to decolonise culture in Britain

-

On free speech, liberal dinosaurs, universal basic income and a video contest

-

Why Democrats are worried about California

-

America is good at dealing with hurricanes on the mainland—after they strike

-

Do we pay nurses less because we envy them? Unlikely

-

How to convince sceptics of the value of immigration?

The idea of a kill-zone may bring to mind Microsoft’s long reign in the 1990s, as it embraced a strategy of “embrace, extend and extinguish” and tried to intimidate startups from entering its domain. But entrepreneurs’ and venture capitalists’ concerns are striking because for a long while afterwards, startups had free rein. In 2014 The Economist likened the proliferation of startups to the Cambrian explosion: software made running a startup cheaper than ever and opportunities seemed abundant.

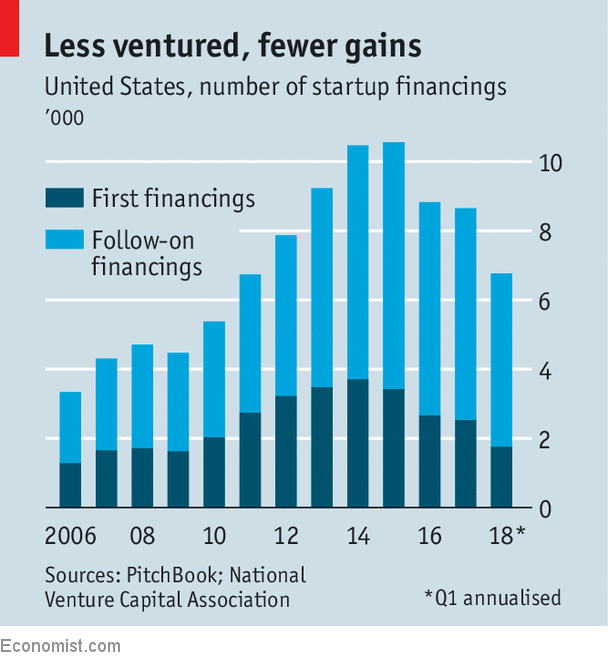

Today, less so. Anything having to do with the consumer internet is perceived as dangerous, because of the dominance of Amazon, Facebook and Google (owned by Alphabet). Venture capitalists are wary of backing startups in online search, social media, mobile and e-commerce. It has become harder for startups to secure a first financing round. According to Pitchbook, a research company, in 2017 the number of these rounds were down by around 22% from 2012 (see chart).

The wariness comes from seeing what happens to startups when they enter the kill-zone, either deliberately or accidentally. Snap is the most prominent example; after Snap rebuffed Facebook’s attempts to buy the firm in 2013, for $3bn, Facebook cloned many of its successful features and has put a damper on its growth. A less known example is Life on Air, which launched Meerkat, a live video-streaming app, in 2015. It was obliterated when Twitter acquired and promoted a competing app, Periscope. Life on Air shut Meerkat down and launched a different app, called Houseparty, which offered group video chats. This briefly gained prominence, but was then copied by Facebook, seizing users and attention away from the startup.

The kill-zone operates in business software (“enterprise” in the lingo) as well, with the shadows of Microsoft, Amazon and Alphabet looming large. Amazon’s cloud service, Amazon Web Services (AWS), has labelled many startups as “partners”, only to copy their functionality and offer them as a cheap or free service. A giant pushing into a startup’s territory, while controlling the platform that startup depends on for distribution, makes life tricky. For example, Elastic, a data-management firm, lost sales after AWS launched a competitor, Elasticsearch, in 2015.

Even if giants do not copy startups outright, they can dent their prospects. Last year Amazon bought Whole Foods Market, a grocer, for $13.7bn. Blue Apron, a meal-delivery startup that was preparing to go public, was suddenly perceived as unappetising, as expectations mounted that Amazon would push into the space. This phenomenon is not limited to young firms: recently Facebook announced it was moving into online dating, causing the share price of Match Group, which went public in 2015, to plummet by 22% that day.

It has never been easy to make it as a startup. Now the army of fearsome technology giants is larger, and operates in a wider range of areas, including online search, social media, digital advertising, virtual reality, messaging and communications, smartphones and home speakers, cloud computing, smart software, e-commerce and more. This makes it challenging for startups to find space to break through and avoid being stamped on. Today’s giants are “much more ruthless and introspective. They will eat their own children to live another day,” according to Matt Ocko, a venture capitalist with Data Collective. And they are constantly scanning the horizon for incipient threats. Startups used to be able to have several years’ head start working on something novel without the giants noticing, says Aaron Levie of Box, a cloud and file-sharing service that has avoided the kill-zone (it has a market value of around $3.8bn). But today startups can only get a six- to 12-month lead before incumbents quickly catch up, he says.

There are some exceptions. Airbnb, Uber, Slack and other “unicorns” have faced down competition from incumbents. But they are few in number and many startups have learned to set their sights on more achievable aims. Entrepreneurs are “thinking much earlier about which consolidator is going to buy them”, says Larry Chu of Goodwin Proctor, a law firm. The tech giants have been avid acquirers: Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Microsoft spent a combined $31.6bn on acquisitions in 2017. This has led some startups to be less ambitious. “Ninety per cent of the startups I see are built for sale, not for scale,” says Ajay Royan of Mithril Capital, which invests in tech.

This can be enriching to founders, who can go on to start another firm or provide financing to peers with smart ideas. To the extent that such exits provide more capital to spur innovation, this is no bad thing. The tech giants can help the firms they acquire grow more than they might have been able to do on their own. For example, Facebook’s acquisition of Instagram took out a would-be competitor, but it has thrived under the social-networking giant’s sway by adopting the technical infrastructure, staff and know-how that Facebook had in place.

Friend or foe?

But plenty of people in the Valley reckon the bad outweighs the good and that early, “shoot-out” acquisitions have sapped innovation. “The dominance of the big platforms has had a meaningful effect on the entrepreneurial culture of Silicon Valley,” says Roger McNamee of Elevation Partners, a private-equity firm, who was an early investor in Facebook. “It’s shifted the incentives from trying to create a large platform to creating a small morsel that’s tasty to be acquired by one of the giants.”

And when startups are bullied into selling, as some are, it is even more worrying. Big tech firms have been known to intimidate startups into agreeing to a sale, saying that they will launch a competing service and put the startup out of business unless they agree to a deal, says one person who was in charge of these negotiations at a big software firm (which uses such tactics).

There are three reasons to think that the kill-zone is likely to stay. First, the giants have tons of data to identify emerging rivals faster than ever before. Google collects signals about how internet users are spending time and money through its Chrome browser, e-mail service, Android operating system, app store, cloud service and more. Facebook can see which apps people use and where they travel online. It acquired the app Onavo, which helped it recognise that Instagram was gaining steam. It bought the young firm for $1bn before it could mature into a real threat, and last year it purchased a nascent social-polling firm, tbh, in a similar manner. Amazon can glean reams of data from its e-commerce platform and cloud business.

Another source of market information comes from investing in startups, which helps tech firms gain insights into new markets and possible disrupters. Of all American tech firms, Alphabet has been the most active. Since 2013 it has spent $12.6bn investing in 308 startups. Startups generally feel excited about gaining expertise from such a successful firm, but some may rue the day they accepted funding, because of conflicts. Uber, for example, took money from one of Alphabet’s venture-capital funds, but soon found itself competing against the giant’s self-driving car unit, Waymo. Thumbtack, a marketplace for skilled workers, also accepted money from Alphabet, but then watched as the parent company rolled out a competing service, Google Home Services. Amazon and Apple invest less in startups, but they too have clashed with them. Amazon invested in a home intercom system, called Nucleus, and then rolled out a very similar product of its own last year.

Recruiting is a second tool the giants will use to enforce their kill zones. Big tech firms are able to shell out huge sums to keep top performers and even average employees in their fold and make it uneconomical for their workers to consider joining startups. In 2017 Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Microsoft allocated a combined a whopping $23.7bn to stock-based compensation. Big companies’ hoarding of talent stops startups scaling quickly. According to Mike Volpi of Index Ventures, a venture-capital firm, startups in the firm’s portfolio are currently 10-20% behind in their hiring goals for the year.

A third reason that startups may struggle to break through is that there is no sign of a new platform emerging which could disrupt the incumbents, even more than a decade after the rise of mobile. For example, the rise of mobile wounded Microsoft, which was dominant on personal computers, and gave power to both Facebook and Google, enabling them to capture more online ad dollars and attention. But there is no big new platform today. And the giants make it extremely expensive to get attention: Facebook, Google and Amazon all charge a hefty toll for new apps and services to get in front of consumers.

Seeing little opportunity to compete with the tech giants on their own turf, investors and startups are going where they can spot an opening. The lack of an incumbent giant is one reason why there is so much investor enthusiasm for crypto-currencies and for synthetic biology today. But the giants are starting to pay more attention. There are rumours Facebook wants to buy Coinbase, a cryptocurrency firm.

Regulators will be watching what the giants try next. Criticism that they have been too lax in approving deals where tech firms buy tiny competitors that could one day challenge them has been mounting. Facebook’s acquisition of Instagram and Google’s purchase of YouTube, before it was obvious how the pair might have taken on the giants, might well have been blocked today. To fight back against the kill-zone, regulators must closely consider what weapons to wield themselves.

Source: economist

American tech giants are making life tough for startups