A LITTLE over a decade ago, when JinkoSolar, a Shanghai-based company, entered the solar business, it was such a novice that when it visited international trade fairs, all it had was a bare table and a board with its name scribbled on it. But it also had luck, a technological edge and lots of public money on its side.

The industry globally was riding high on subsidies. Generous feed-in-tariffs (FITs), financial incentives for installing solar, made Germany the world’s largest solar market by around 2010. Germans turned to China for cheap sources of crystalline silicon solar panels, not least because subsidised land and loans enabled China’s fledgling manufacturers to undercut European and American competitors.

-

Some thoughts on the crisis of liberalism—and how to fix it

-

Why Germany’s rent brake has failed

-

Why predicting the winner of the World Cup is so difficult

-

The ECB puts an expiry date on quantitative easing

-

Civil war breaks out on Germany’s centre-right

-

Nearly one-fifth of Americans would deny their country’s Muslims the right to vote

When European solar subsidies slumped during the euro crisis, the Chinese government once again stepped in to support its renewable-energy champions. It offered FITs to slather the remote west of China with solar farms. By 2013 China had eclipsed Germany as the world’s largest solar-panel market; last year it installed 53 gigawatts (GW), almost five times as much as in America, now the next-biggest market. Jinko became the world’s largest provider of solar panels in 2016, shipping almost 10GW globally last year. Six of the top ten producers are Chinese.

These ups and downs are known globally as the “solarcoaster”: just as subsidies can quickly build the market up, their withdrawal can tear it down. On June 1st this happened with a particularly heart-stopping lurch when Chinese authorities, with almost no notice, strictly limited new solar installations that qualified for FITs, blitzing the shares of Jinko and some of its peers in China, as well as of First Solar, one of America’s biggest solar suppliers.

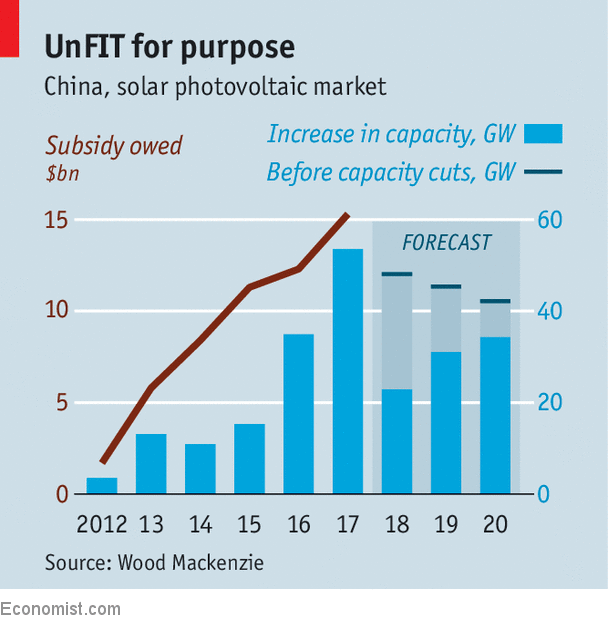

Analysts reckon that at least 20GW of solar projects expected to be built in China this year will now be scrapped (see chart). As demand wilts, they predict, Chinese panel prices will fall by at least a third. Benjamin Attia of Wood Mackenzie, an energy consultancy, says that, depending on how quickly the price falls encourage an uptake of solar in new markets, this could be the first year since 2000 that the global solar industry stalls. “In the short term, the policy change will rack the China market with angst,” says an industry insider there.

The clampdown comes at a time when the solar industry globally is increasingly able to compete toe-to-toe on price with more conventional sources of power generation, such as coal, natural gas and nuclear. Countries in Europe, including Britain and Spain, and elsewhere too, have drastically slashed FITs. It all raises an important and tricky question: is this the end of the line for solar subsidies?

China provides an illustration of the likely answer, which is that FITS may be disappearing but other subsidy-lite alternatives are taking their place. Analysts say China’s decision to scrap FITs follows a rise to about $15bn last year in the deficit in the subsidy fund earmarked for developers; plugging the gap would have strained public finances. As a result of this shortfall, solar developers were not getting the subsidies they were owed. As one industry insider puts it, everyone loves subsidies—but only when they get paid.

Paolo Frankl of the International Energy Agency, a global forecaster, notes that China had recently begun to experiment, via a programme called “Top runner”, with an alternative to FITs that is gaining popularity internationally. This is a reverse auction in which solar developers that offer to build and run projects most cheaply win. The price they bid is what they will charge in long-term power-purchase agreements (PPAs) for the electricity they generate. Such reverse-auction PPAs have produced startlingly low bids in sunny places from Arizona and Nevada to Mexico, Abu Dhabi and India. In China recent PPAs sharply undercut the FITs, he says. One even beat coal-fired power. Hence China’s aim to encourage more of such auctions to make solar, on the face of it, subsidy-free. The benefits could be significant in China. Lower prices of panels as a result of a temporary glut will encourage more aggressive bids, saving the government money and making solar more competitive against coal.

Yet though few doubt that PPAs are better than FITs, there is still fierce debate about whether they are also a sort of market-distorting subsidy. For instance, utilities may be forced to offer renewable PPAs, rather than fossil–fuel alternatives, because governments hold them to renewable-energy targets. The very existence of long-term contracts may make it cheaper for solar developers to get funding than they would otherwise. That said, it is hard these days, in China or elsewhere, to build any power plant without some public support. And purists say that any fossil-fuel project that goes ahead without taxing the carbon it produces is also enjoying an implicit subsidy.

China’s move—though it will stall new solar installations for a while—may nonetheless make the global industry healthier over time. The shift may hasten consolidation in the industry in China, bringing the four main manufacturing components, polysilicon, wafer, cell and panels, under one roof, as they are at Jinko.

Bloomberg New Energy Finance, a consultancy, says that by 2019 more markets may embrace solar, given the fall in panel costs. The cheaper solar gets, the more appealing it becomes, especially in poor countries struggling to satisfy rising energy demand. Mr Attia of Wood Mackenzie notes that pre-qualified bidders for a solar tender in Kuwait, announced after June 1st, involved Chinese property, mining and defence firms, which are not usually associated with photovoltaics (PVs). They may opportunistically be attempting to shift a surfeit of Chinese PV abroad.

The price cuts may also give Chinese solar manufacturers, stung by 30% tariffs imposed by the Trump administration in January, an opportunity to regain competitiveness in America (which maintains subsidies of its own via tax credits). The tariffs kept their silicon PV products out of the American market, bolstering sales of First Solar. But a fall of 30% or more in PV prices should make the tariffs less of a hindrance. Analysts say that is why First Solar’s shares have fallen by a fifth since June 1st.

Solar experts expect the solarcoaster to rattle out of its current trough. But the ride still has a long way to go. Though solar was the world’s biggest source of new power-generating capacity last year, it still generates a paltry 2% of global electricity. Technological improvements to make it better at turning sunlight into energy are slowing down. Here again, China offers a lesson. Its “Top runner” programme rewards those companies experimenting with the latest PV technologies, in a bid to make solar more competitive. Jinko says no other country offers such a scheme. The shame is that it is only open to Chinese firms.

Source: economist

Can the solar industry survive without subsidies?