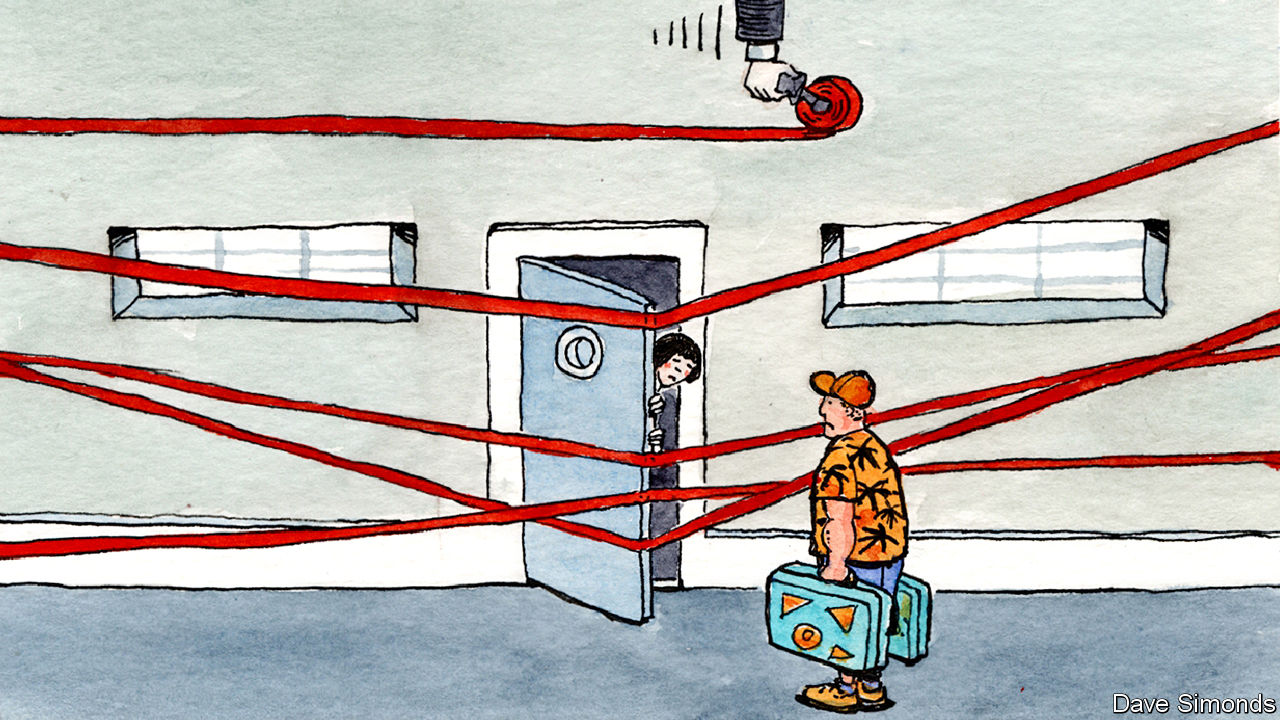

AIRBNB, an American platform for booking stays in other people’s houses, can barely conceal its frustration. A law passed last year for the first time legalised minpaku, or home-sharing, in Japan, but also sharply restricted it. From June 15th hosts can rent out their property for a maximum of 180 days each year, provided they register with the local authorities. Most hosts will not meet that deadline because they are still obtaining their registration numbers, and on June 1st Japan’s main tourism body unexpectedly decreed that any without them had to cancel reservations at once. Airbnb accordingly eliminated four-fifths of its roughly 60,000 listings in Japan. Holidays are at risk.

The experience illustrates the country’s hesitant approach to the sharing economy, in which people rent goods and services from one another through internet platforms (a broader definition includes companies renting out goods they own, such as bikes, for a short time). A generous estimate of the sharing’s economy value in Japan is just ¥1.2trn yen ($11bn), compared with $229bn for China. “It’s a very difficult situation,” says Yuji Ueda of Japan’s Sharing Economy Association.

-

Some thoughts on the crisis of liberalism—and how to fix it

-

Why Germany’s rent brake has failed

-

Why predicting the winner of the World Cup is so difficult

-

The ECB puts an expiry date on quantitative easing

-

Civil war breaks out on Germany’s centre-right

-

Nearly one-fifth of Americans would deny their country’s Muslims the right to vote

Opportunities certainly abound. Almost 29m tourists visited Japan last year; the goal is to attract 40m by 2020, when Tokyo hosts the Olympics. But the number of hotel rooms is not keeping up with demand. Japan’s government reckons that sharing could also help it to provide public services such as transport, especially in rural areas, as it struggles with a declining and ageing population.

Successes do exist. There are thriving platforms to share meeting rooms, office space and parking spots. One popular site is Laxus, which lets cash-poor city dwellers share designer handbags. Airbnb’s own offering of “experience sharing”, in which people sell and buy experiences such as city tours and cooking classes, is more successful in Japan than almost anywhere else, says Mike Orgill, its head of policy in Asia, as foreigners in particular seek a window into the country.

Yet regulation, which tends to favour big companies and industries, is a key obstacle to faster and more mainstream growth. The minpaku law’s 180-day limit, which local authorities have the right to tighten further, is a nod to powerful hotel chains. Shinjuku, a ward in Tokyo that is popular with visitors, is banning home-owners in residential areas from renting out their homes from Mondays to Thursdays. Uber, a ride-hailing firm, is prevented from offering anything but its premium services, such as black cars with professional drivers, thanks in large part to the objections of established taxi fleets. There are ways to get round it—a local ride-sharing app, Notteco, has avoided the regulations by getting passengers to pay for petrol and tolls rather than a fee for transport, for example. But the rules hinder growth.

Another hurdle is the attitude of the Japanese public. Many people are simply ignorant of the existence of sharing apps. Others reckon they may be illegal. “Public anxiety is the main factor impeding the development of the sharing economy,” thinks Yusuke Takada of the government’s Sharing Economy Promotion Office. Another barrier is social custom. Chika Tsunoba, the head of Anytimes, a local platform where users share skills from gardening to baby-sitting, says women in particular feel they should be doing everything themselves, pointing to criticism she attracted after hiring a cleaner through the site. Mr Ueda says the Japanese fret that sharing platforms will not provide the high level of service they are accustomed to. Because of this, the Sharing Economy Association has developed a “trust mark” to give consumers more confidence.

International firms are also adapting their tactics. Airbnb is “partnering with areas that don’t get as much love as they might like,” says Mr Orgill. It worked with the authorities and locals in Kamaishi, on the north-east coast, to attract tourists, even creating a local guidebook. As for Uber, helping established firms is not something the firm does anywhere else, notes Ann Lavin, who heads policy in Asia-Pacific for the firm, but it is piloting a ride-hailing programme for local taxis on the remote island of Awaji, near the city of Kobe. This caring, sharing approach may pay off, but it will take more time.

Source: economist

Why Japan’s sharing economy is tiny