A PUBLIC spat between two warring and wildly popular Chinese apps has had the feel of a teenage dance-off. “Sorry, Douyin Fans”, ran an article from the short-video app on its WeChat account, in which it accused the mobile-messaging service of disabling links to Douyin’s most popular videos. “All hail Douyin the drama queen,” retorted Tencent, WeChat’s parent, which said it had acted because the content was “inappropriate”.

-

Why Japan is going to accept more foreign workers

-

Arab states are losing the race for technological development

-

Why art exhibitions are returning to domestic settings

-

Transcript: Interview with General Mark Hicks

-

Trans-inclusive feminist voices are being ignored

-

A British traveller’s travelogue

On June 1st Tencent sued Douyin’s parent company, Bytedance, for 1 yuan (15 cents) and demanded it apologise for its accusations—on its own platforms (and presumably without the snark). Tencent also alleged unfair competition. Within hours Douyin counter-sued for 90m yuan. Bytedance and Tencent later swapped accusations of tolerating smear campaigns against the other on their apps, and filed police reports about defamatory posts.

Rarely has an upstart so piqued Tencent, a Chinese gaming and social-media titan which in November became Asia’s first company worth over half-a-trillion dollars. At first blush WeChat and Douyin (which translates as “trill”) appear to inhabit distinct worlds. The former is a super-app in which more than 1bn users not only chat but also order food, give to charity and pay utility bills. Douyin is a bottomless, eclectic feed of looped 15-second videos, a cross between Snapchat, Vine (now defunct) and Musical.ly, which Bytedance bought in November. The clips, shot by users, range from a dexterous noodle-maker in Chongqing to a shimmying peacock in a bamboo grove, all set to music.

Different though the services are, Bytedance’s use of artificial intelligence to create tailored offerings for each viewer on Douyin—and on Toutiao, a newsfeed—is winning attention. According to QuestMobile, a data vendor, in early 2017 users began to spend more time on Toutiao, Douyin and two other Bytedance video apps, Xigua and Huoshan, than they did on Tencent’s news and video offerings.

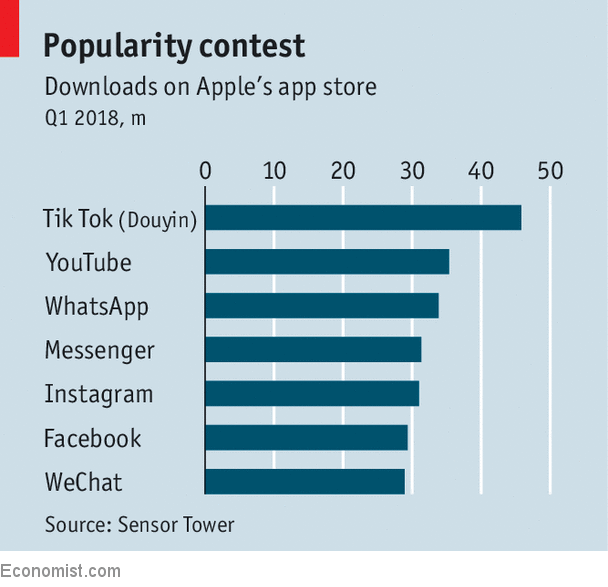

In the first quarter of this year Tik Tok, an international version of Douyin that launched in late 2017, became the world’s most downloaded iPhone app, excluding games (see chart)—a rare feat for a Chinese social app. It has done well in Indonesia and Thailand. At home it led app-store rankings from January to May. It claims to have a user base of 300m in China, more than Kuaishou, another short-video app in which Tencent has a stake. Its appeal has prompted Communist Party outfits to set up accounts, and, on one occasion, state censors to place restrictions on it.

All of which has provoked Tencent into providing a “defensive product”, notes Xue Yu of IDC China, a consultancy. In April Tencent resuscitated its short-video app, Weishi, a year after closing it. Its angst may stem from the fact that every firm wants “a top-of-mind app”, says Anu Hariharan of Y Combinator, a Silicon Valley startup school, and a personal investor in Toutiao.

WeChat has hardly lost its oomph. A state agency recently reported that WeChat made up 34% of China’s total mobile-data traffic in 2017. To advertise, Douyin still relies on users sharing its videos on WeChat’s public feeds (hence its ire over the blocked videos). Still, the share of time spent by Chinese mobile users on messaging slipped from 37% to 32% in the year to March, says QuestMobile, while that spent on watching short-form video has risen from 1.5% to over 7%. Meanwhile, Douyin has introduced its own private-messaging function, further challenging WeChat.

In May an essay put out on WeChat by a former tech journalist lit up social media. In “Tencent Doesn’t Have a Dream” he argued that the firm had become chiefly an investment firm buying up other startups and had lost its innovative edge. One bit of evidence was that by the time Tencent had registered Douyin’s rise, its window for a counter-attack had all but closed. The naysayer claimed his treatise drew 1m views. Still, his readers all came to WeChat.

Source: economist

A Chinese music-video app is making WeChat sweat