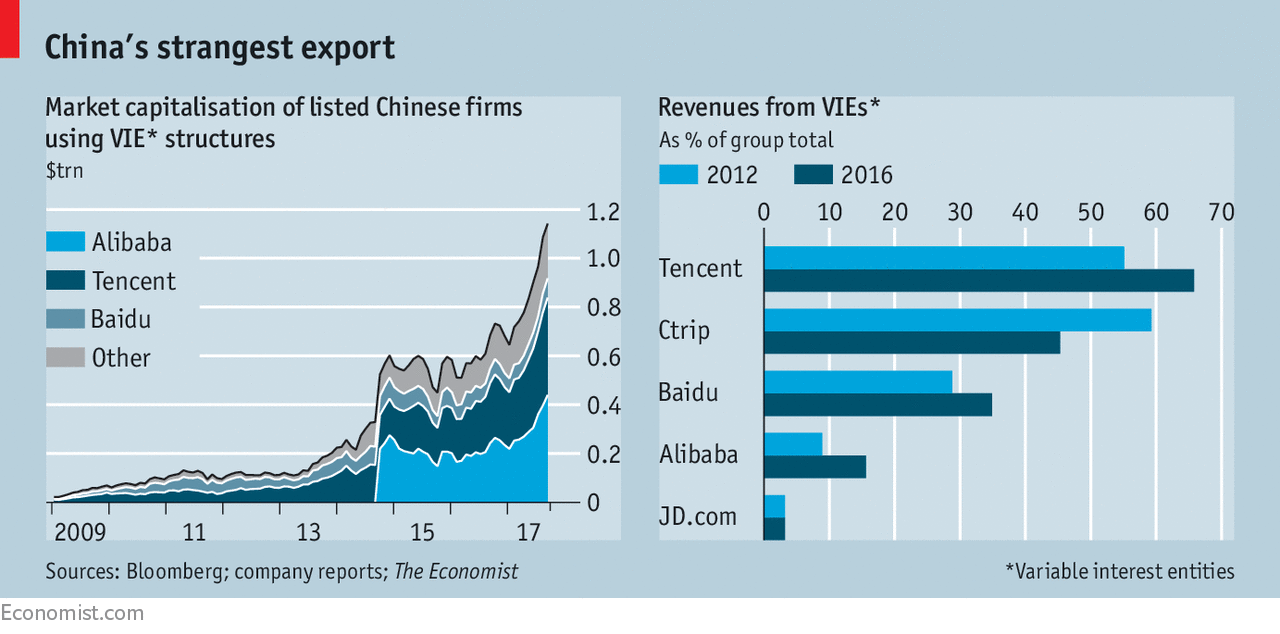

COMPANIES’ legal structures are usually mind-numbing fare. But occasionally it is worth pinching yourself and paying attention. Take “variable interest entities” (VIEs), a kind of corporate architecture used mainly by China’s tech firms, including two superstars, Alibaba and Tencent. They go largely unremarked, but VIEs have become incredibly important. Investors outside China have about $1trn invested in firms that use them.

Few legal experts think that VIEs are about to collapse, but few expect them to endure, either. One sizeable investor admits loving Chinese tech firms’ businesses while feeling queasy about their legal structures. Like scientists appalled by their monstrous creations, even the lawyers who designed VIEs worry. They are “China’s version of too-big-to-fail”, says one. As well as being spooky, VIEs are another instance of how China’s weak property rights hurt its citizens.

-

The Gates Foundation is worried about the world’s health

-

Retail sales, producer prices, wages and exchange rates

-

Foreign reserves

-

Why Italy’s troubled economy is returning to form

-

Sorry, Roger: Rafael Nadal is not just the king of clay

-

Sam Brownback, governor of Kansas, heads for the exit

What are VIEs? Over 100 companies use them. Since the 1990s private firms have sought to break free of China’s isolated legal and financial systems. Many have done so by forming holding companies in tax havens and listing their shares in New York or Hong Kong. The problem is that they are then usually categorised as “foreign firms” under Chinese rules. That in turn prohibits them from owning assets in some politically sensitive sectors, most notably the internet.

The lawyers’ quick fix, first used in 2000, was to shift these sensitive assets, such as operating licences, into special legal entities—VIEs—that are owned by Chinese individuals, usually the firms’ bosses. The companies sign contracts with the VIEs and their individual owners, which the companies say guarantees them control over the VIEs’ assets, sales and profits. Abracadabra!

Alibaba, the world’s sixth-most valuable firm, illustrates how it works. It is incorporated in the Cayman Islands and in 2014 listed its shares in New York, but makes 91% of its sales in mainland China. There it owns five big subsidiaries which have contracts with five corresponding VIEs. The VIEs contain licences and domain names and are owned by Jack Ma and Simon Xie, two of Alibaba’s founders. It is as if Facebook were domiciled in Samoa, listed in Shanghai and its website and brand sat in separate legal entities that were the property of Mark Zuckerberg (but which he had agreed to allow Facebook to run and profit from).

American regulators allow VIEs if their dangers are disclosed. Although most VIE schemes have worked smoothly, the underlying risks have risen in the past five years. It is unclear if VIEs are even legal in China. The latest annual reports of the ten largest firms that use them all admit to uncertainty about their status. In 2015 a draft reform from the Ministry of Commerce appeared to ban some VIEs, but the initiative has gone nowhere.

Meanwhile, VIEs have become more prominent; the total value of companies that use them has soared as China’s internet industry has boomed. The share of firms’ sales generated by their VIEs varies but for most of the ten companies has risen since 2012 (see charts). The inner workings of the VIEs are often in flux. In nine cases, their structure has changed in that period: either the names or number of entities, or the names or stakes of their Chinese owners, have been altered. If they are being honest, most shareholders have little idea what is going on.

For investors, there are two risks. First, the VIEs could be ruled illegal, potentially forcing the firms to wind up or sell vital licences and intellectual property in China. The second danger is that VIE owners seek to grab the profits or assets held within. If they refuse to co-operate, die, or fall out of political favour, it is far from clear that firms can enforce VIE contracts in Chinese courts.

Yet this manifestly flawed system has endured for two decades. One theory is that managers favour it because it gives them more power—it is hard for outside shareholders to keep track of VIEs. Like their peers in Silicon Valley, who limit voting rights, China’s tech tycoons dislike it when investors call the shots.

The bigger question is why China’s government tolerates the set-up. Perhaps it suits high officials to keep the country’s internet bosses on an ambiguous legal footing, so that they toe the line. VIEs could even be a diplomatic tool. In the event of a trade war, a quick way to hurt Americans’ economic interests (along with banning Apple, which makes a fifth of its sales in China) would be to void VIEs, although China’s reputation with all investors would suffer.

Unscrambling eggs

But failing to tackle the status quo has wider costs, chief of which is that having internet firms listed abroad means most Chinese citizens cannot invest in the most dynamic bit of their economy. It is easier for a pensioner in Dundee to invest in firms in the world’s most exciting e-commerce market than it is for one in Dalian. Shanghai’s stock exchange is full of stodgy state-backed companies. So far, foreigners have made a capital gain of at least $500bn from China’s internet sector, while locals have been all but shut out. Imagine if Americans could not invest in Apple, Amazon, Facebook or Alphabet. As China’s internet firms get bigger, the unfairness of this will become ever more glaring.

VIEs need to be unwound. Some small internet firms have bought back all their shares and delisted in America, then relisted in mainland China, but the cost of this for the big firms would be prohibitive. Alternatively, they could create dual listings in Shanghai or float the shares of their subsidiaries there for locals to invest in. Yet the question of their VIEs’ legality would linger.

The enduring answer is for China to relax its foreign-ownership restrictions and open its capital account. Both foreigners and locals could buy into internet firms with a solid legal footing. Whether it does is a test of its appetite for creating an economy based on rules, not fiat. Until then VIEs are the financial equivalent of the “One China” principle that governs China’s relations with Taiwan, which the mainland considers a renegade province—a polite legal fiction that papers over serious problems. Such quick fixes can seem stable. But in the back of your mind there is a rational fear that they could blow up at any time.

Source: economist

A legal vulnerability at the heart of China’s big internet firms