EIGHT months into Donald Trump’s presidency, the rules-based system of global trade remains intact. Threats to impose broad tariffs have come to nothing. Some ominous investigations into whether imports into America are a national-security threat are on hold. Mr Trump looks less a hard man than a boy crying wolf. All the same, supporters of the World Trade Organisation (WTO), the guardian of that rules-based system, are worried. Other dangers are lurking. There is more than one way to undermine an institution.

The WTO is meant to be a forum for reaching deals and resolving disputes. But all 164 members must agree to new rules, and agreement has largely been elusive. So if members do not like today’s rules, as interpreted by judges, they have little prospect of negotiating better ones. That puts pressure on the WTO’s judicial function, the bit that has been working fairly well.

Trouble is brewing at the WTO’s court of appeals. It is meant to have seven serving judges, but has only five and by the end of the year will have just four. The Americans refuse to start the process of filling the spots, citing systemic concerns. What seemed an arcane procedural row has become what some call a “crisis”.

-

Retail sales, producer prices, wages and exchange rates

-

Foreign reserves

-

How taxes can align the interests of individuals and society

-

The case against shrinking the Fed’s balance-sheet

-

Can companies block employees’ class-action lawsuits?

-

Kenya’s supreme court explains why it annulled last month’s presidential poll

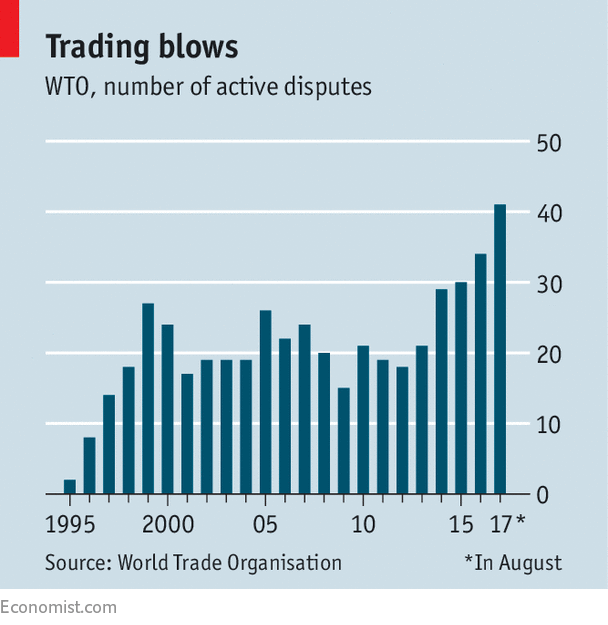

This tension comes at a bad time. Over recent years the number of disputes has risen both in number (see chart) and complexity. The court is already dealing with a backlog of cases, which are supposed to take two months. One appeal from the EU, relating to Airbus, an aircraft manufacturer, is almost a year old. By the end of 2019 the terms of two more judges will expire, leaving only two. Three are needed to rule on any individual case. If the gaps are not filled, the system risks collapse.

Notionally, the Americans object to two procedural irregularities, including the way the most recently departed judges left. But according to Brendan McGivern, a lawyer in Geneva, neither is a “show-stopping” problem. And on September 18th Robert Lighthizer, America’s usually tight-lipped trade representative, outlined a bigger agenda. To a Washington room packed with foreign-policy wonks, he complained that decisions from WTO judges had “diminished” what America had bargained for and imposed obligations it had not agreed to when it joined the WTO.

These are long-standing and uniquely American concerns. Panels at the WTO have repeatedly ruled that the way it calculates defensive duties on imports breaks the rules. Mr Lighthizer sees this as undermining America’s ability to protect itself from unfair trade. Many in Washington accuse the WTO’s lawyers of overstepping their remit, filling in the gaps where the original rules are silent.

So the American administration seems in effect to be using the judicial appointments to hold the WTO hostage. Oddly, though, it has been vague about what it wants. Mr Lighthizer’s past offers clues. According to the Wall Street Journal, when he advised Bob Dole, a presidential candidate in 1996, he recommended that a panel of American judges should review any findings against America, which would threaten to quit the WTO after three duds. This week Mr Lighthizer spoke fondly of the system that preceded the WTO, under which members could block panel rulings.

Bullying the appellate body into ruling in favour of America would undermine its usefulness. If members no longer think that they will get a fair hearing, they are more likely to take matters into their own hands. Mr McGivern worries that an American fix to the perceived problem of judicial overreach could undermine the rules-based system, by tampering with the independence of the appellate body.

Some signs suggest that Mr Trump’s administration is not planning to ditch the WTO entirely. It is pursuing two disputes initiated by Barack Obama. And Mr Lighthizer has said that if he uncovers a breach of China’s commitments under WTO rules, he will file a dispute. But he expressed doubt about the WTO’s ability either to deal with Chinese mercantilism or to reach any agreements at its next ministerial meeting in December.

Mr Trump’s tough-cop trade policy appears to be to threaten tariffs unless he gets his way. Mr Lighthizer’s is subtler but perhaps more menacing. By combining indifference with a ploy to starve the WTO of judges, he is gambling that the WTO needs America more than America needs it. In both cases the risks are the same: that the rule book will become irrelevant.

Source: economist

America holds the World Trade Organisation hostage