WHO wants mediocrity? That is what a lot of people say when the subject of index-tracking, or passive fund management, comes up. They would rather choose a fund manager (an active manager in the jargon) who tries to beat the market by picking the best stocks. It does sound like a good idea.

The tricky bit is finding the right manager. The temptation is to look at past performance but fund managers rarely beat the market for long.

-

An evening with Momentum at the Labour Party conference

-

Picking a fund manager? The odds aren’t great

-

The American embassy building in London is a modernist classic

-

Online auctions of Boeing 747s reflect shifts in the air-travel industry

-

Why the referendum on Catalan independence is illegal

-

Anthony Weiner is sentenced to 21 months in prison

The average fund manager is always going to struggle to beat the market (this is a separate argument from whether markets are “efficient”). That is because the index reflects the performance of the average investor before costs. In a world dominated by professional fund managers, there aren’t enough amateurs for the professionals to beat. Even the hedge funds, those supposed “masters of the universe”, haven’t been able to do it; Warren Buffett looks set to win a $1m bet on the issue.

But the last 12 months have seen a revival of the fortunes of active managers and there is talk that the cycle has turned. Individual stocks seem less correlated with each other than during the 2010-2015 period; small stocks, which aren’t included in some indices, are doing well. In Britain, a very high proportion of funds beat the market over the last year; US funds also seem to have done so well.

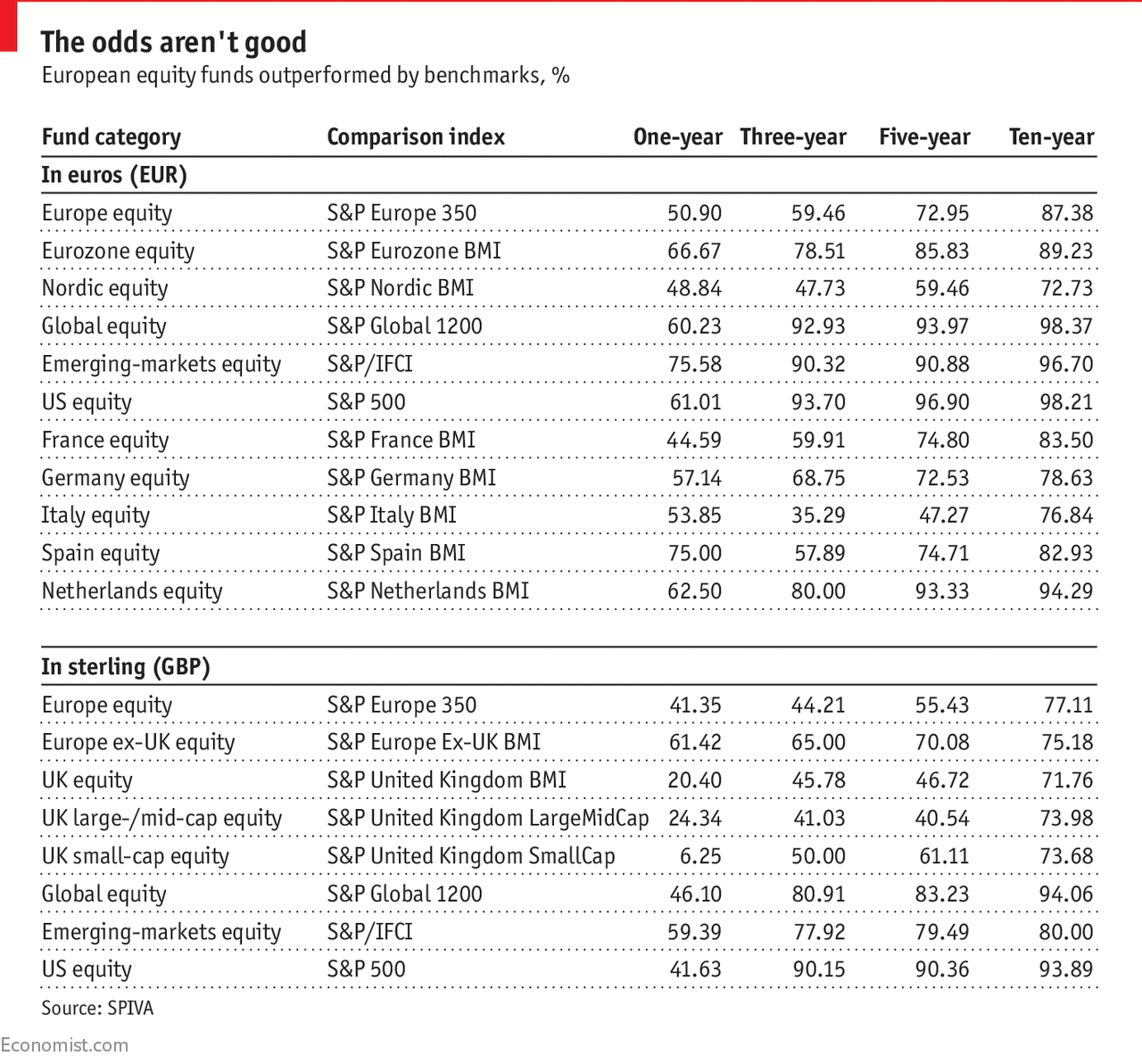

The table, from Standard & Poor’s, shows how many European-domiciled funds (investing in a wide range of markets) have managed to beat the market over 1, 3 , 5 and 10 years. Eight out of 19 categories managed the feat over one year, but that drops to 4 categories over 3 years, three over 5 years and none over 10 years. In most categories over 10 years, you had a less than 1-in-5 chance of finding a fund that beat the market.

So why do so many people think they can pick a winner? The answer may be found in a new paper from James White, Jeff Rosenbluth and Victor Haghani of Elm Partners that shows people find it very difficult to tell skill from luck. Suppose you have two coins, one fair and the other biased 60% in favour of heads. How many parallel tosses would you need to be 95% certain (statistically speaking) of identifying the rigged coin? They asked 700 financial professionals the question and their median guess was 40. The actual answer is 143. If you widen the experiment to three coins, the number rises to 220.

The authors then use a thought experiment, which assumes that 15% of fund managers can generate a post-fee return of 1% a year relative to the market while the other 85% lose 1%. They put 1% of the portfolio a year into each fund and then shift more to the winners each year, based on the probability that they can continue to outperform. Even after 10 years, the expected return on this portfolio is -0.6% a year, relative to the index.

There is even more bad news. At least, a coin doesn’t know whether the last result as a head or a tail. Investment success is affected by past data; other people copy a winning strategy and stocks can move from cheap to expensive as they outperform. The authors add

Sadly, the power of past returns to predict the future is even weaker in investing than it is with coin flips. In the real world, any kind of return-chasing strategy will face additional headwinds, amongst them the fact that when an investment strategy was truly extraordinary in the past, its very discovery will diminish future performance (or even make future returns negative), as more capital is drawn towards it. This may be the prime reason why investor returns (i.e. dollar-weighted returns) tend to be significantly below fund returns (i.e. time-weighted returns). This doesn’t happen with coin flips.

To sum up, you may think you can pick a successful active manager. But the laws of probabbility suggest you can’t.

Source: economist

Picking a fund manager? The odds aren't great