Investors in U.S. stocks are surely pleased with their gentle climb this year. But do they truly appreciate just how extraordinarily generous the market has been?

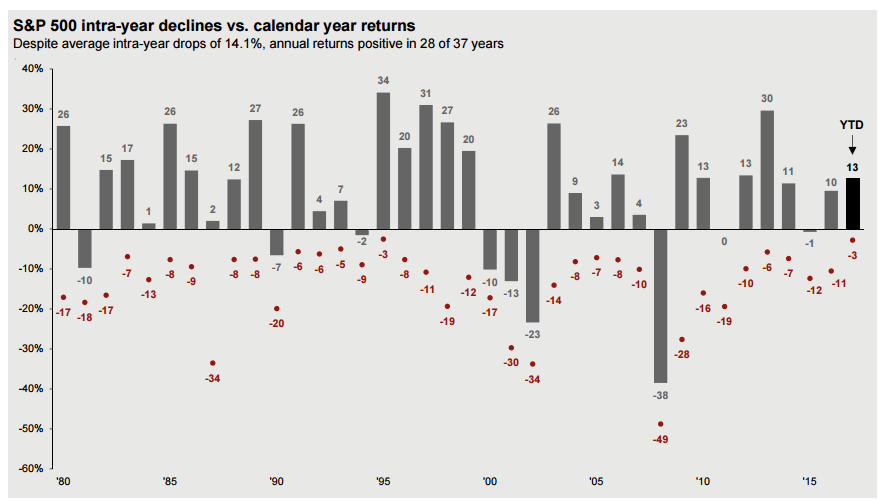

The amount of upside gain with hardly any downside pain so far makes 2017 one of the best buy-and-hold environments of recent decades. The S&P 500 is up 14 percent year to date, not including dividends. Its deepest pullback, if one can call it that, was a 3 percent slip over a four-week stretch in March.

That’s a 4.6 ratio of upside to downside, and if the year-to-date gains were annualized to 17.8 percent without more than a 3 percent intervening drop, the ratio approaches 6.

This places 2017 alongside two of the most effortlessly profitable years in modern market memory – 2013, when the 30 percent surge came with a maximum setback of 6 percent along the way, and 1995, a nirvana year for stocks when a 34 percent return came with a mere 3 percent wobble.

Source: FactSet; J.P. Morgan Asset Management

A few observations about some common threads running through the years 2017, 2013 and 1995: Each followed an anxious, treacherous market environment the year before and reflected a prolonged release of built-up tension and investor risk aversion.

The year before the 1995 mega-rally, the Fed had engineered the 1994 bond market crash. The 2012 election, European debt-crisis aftermath and “fiscal cliff” budget battle preceded the 2013 advance. And last year, we had the compound stress events of an industrial and earnings recession, the oil crash, Brexit and a hyper-contentious election.

These rally years all took place when central banks were arguably “easier” than a strengthening economy warranted. They were all “gridlock years” in Washington, with government shutdowns in ’95 and ’13, and so far stymied fiscal-policy efforts this year. And, for whatever it’s worth, neither of the prior two years was at or very near a market peak.

So where does that leave the outlook for the rest of this year and beyond?

Well, a clear difference between those prior sweet years and this one is the magnitude of the upside. This year has been a steady, orderly march higher rather than a sprint up a steep grade. Both ’95 and ’13 had very good fourth quarters. And the record generally shows that markets, such as the current one, that make new highs in September and don’t succumb to “typical” weakness in August-September tend to finish the year strong.

So it’s perfectly logical to expect further upside as investors take comfort in globally harmonious growth, accelerating industrial indicators in the U.S., a continued earnings rebound, remarkably accommodative credit markets and a possible performance chase into year-end.

The key question at the moment, though, is where the border sits between “all is good” and “as good as it gets” or even “too much of a good thing.”

Jeff deGraaf, chairman and chief technical analyst at Renaissance Macro Research, is telling clients this week the risk of a “melt-up” in stocks is “very real.”

“Given the good economic data, loose credit conditions, benign inflation data and investor’s sentiment, we think the risks of the Fed (and G7 central banks) blowing an asset bubble are above average,” he says. Cyclical indicators such as the ISM purchasing managers index above 60, with unemployment under 4.5 percent, are arguably “too good,” correlating with poor 12-month returns for stocks. “But until credit conditions deteriorate, we’re holding on to this tiger’s tail,” deGraaf concludes.

An economy running hot, a Fed fixated on soggy inflation data and investors prepared and equipped to keep lifting equity exposure are a formula for some kind of upside overshoot, by this analysis.

This would imply, though, that if the market perceived the Fed moving faster to tighten financial conditions – under Chair Janet Yellen or a soon-to-be-picked successor – the melt-up setup could be challenged.

One other thing to keep in mind: Strategas Group fixed-income strategist Tom Tzitzouris says speculative-grade corporate debt and equities are now “co-dependent” to an unusual degree. He argues that high-yield corporate bonds now look a bit rich, with most of the overvaluation attributable to very low stock-market volatility. Stock investors are looking at strong credit markets and concluding all is fine, as credit investors are taking comfort in the equity calm and keeping risk spreads tight.

The upshot: Junk-bond “spreads will likely correct WITH equities, not before, and it lessens the lead time that a HY selloff will provide to equity investors.”

It’s a late-cycle market backdrop in the U.S., by most measures. But no one knows exactly how long it can stay late.

After feeding on investor caution and skepticism most of the year, the market has been good enough to stretch many investors and indicators toward excess optimism. The Daily Sentiment Index of S&P 500 index-futures traders hit 89 bullish on a 100 scale Wednesday. The CNN Money Fear & Greed Index of market-based risk-appetite gauges is at a searing-hot 95 on its 100 scale.

The CBOE’s S&P 500 Volatility Index is flirting with all-time closing lows, mostly reflecting the sleepy pace of the underlying market. Yes, this implies the market is getting overbought and could hit an exhaustion point or quick shakeout soon.

But the folks who typically bet on such switchbacks have been chastened, and so far this year sentiment extremes have meant mere pauses followed by further upside, rather than punishing downturns. So the all-gain, no-pain market abides, for now.

Source: Investment Cnbc

Steady rally ranks with all-time best, but is this as 'good as it gets'?