WHEN a revolution happens, the consequences are not obvious straight away. The British referendum on EU membership in June 2016 was seen as a revolt of ordinary people against a globalised elite. The politicians who led the Leave campaign did not seem to expect to win; as wags remarked, they were like “the dog that caught the car”.

This helps to explain the general chaos that has enveloped British policy since the result. The Leave campaign had contained two contradictions. The first was that Britain could have all the advantages of EU membership without the bother of actually belonging; the country could “have its cake and eat it” as Boris Johnson, Leave campaigner and now foreign secretary put it. The second was the split between the free market, Liberal brexiters, who envisaged Britain as open to the world, and the nativist camp led by Nigel Farage.

-

When the revolution eats itself

-

How two local referendums might affect Italy’s future

-

An unwelcome rise in obesity

-

Bosnia’s stand-ups jest about genocide

-

Transcript: Interview with Hillary Clinton

-

A bomb blast in Somalia’s capital exposes the government’s failures

Theresa May, who took office as prime minister in the wake of the referendum, has struggled to reconcile these two camps. It took Britain a long time to trigger the Article 50 process for leaving the EU and the talks have since got bogged down (as Leavers insisted they wouldn’t be) on issues such as the size of the financial commitments the UK should continue to meet.

Impatience is rising and the leadership is turning on itself. One camp wants Mrs May to sack Mr Johnson, who has been writing articles clearly dissenting from the government line; another camp wants to see the back of Philip Hammond, the chancellor, who is taking a cautious view of post-Brexit economic prospects. It seems likely that Mr Hammond is paying attention to the concerns of those in business and finance who expected Britain to take a pragmatic approach. Instead the ideologues are outflanking the pragmatists.

But it is not clear whether the government can afford, politically, to do what business leaders want: settle the bill with the EU and stay in the single markets and customs union. Brexiters will see this as a betrayal. And the Conservatives will get no help from the Labour party, which has a clear political interest in seeing the negotiations fail. The party can simply demand that the government deliver on the Leave campaign promises, knowing that this will be impossible.

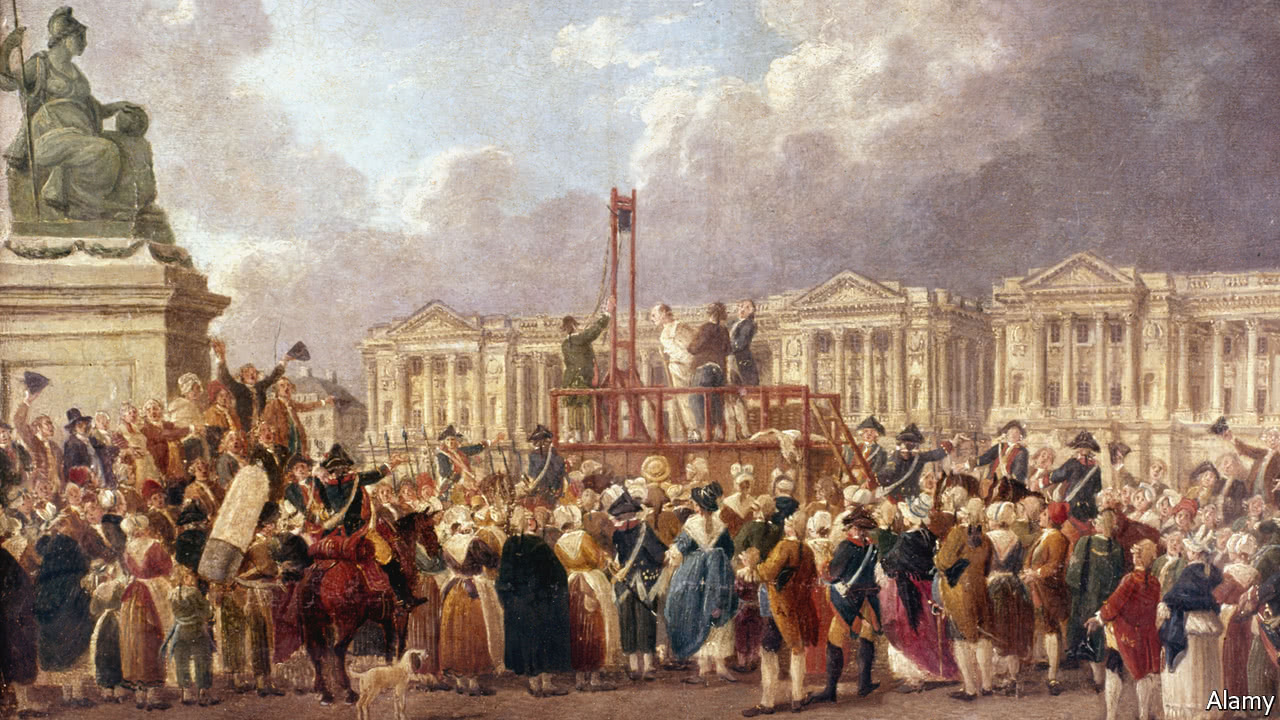

We are at the stage of the battle between the Girondins and the Jacobins in the French revolution. The Girondins may have helped to bring down Louis XVI but they found themselves outflanked by the Jacobins who in turn were consumed by the violence they unleashed. There is now lots of talk of “no deal”, creating the risk of a chaotic breakdown in trade, with backlogs of lorries from Dover to the M25. This is crazy stuff. While the Conservatives are battling with each other, the only cause they are serving is that of Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour party.

Let me sketch out a plausible outcome. In a last minute-deal in early 2019, Mrs May gives in on the main issues to the EU—on money, the European Court of Justice and migration. This is seen as a betrayal by her backbenchers, who force her out. A new prime minister takes over. That person calls an election—possibly on the grounds of repudiating the deal or merely to give themselves a mandate. With the Conservatives in a mess, Labour sweeps to power with a manifesto promising higher taxes on individuals and companies, nationalisation and changes to the labour market to enhance workers’ rights.

This is where the economic and political risk comes in. In the aftermath of the referendum, the pound plunged but the UK stockmarket did fairly well (in local currency terms) because of the overseas earnings of many listed companies. Since then, it has been pretty clear that the markets have been happiest when a deal with the EU looks more plausible. But a post-Brexit, Corbyn-led Britain would prompt international investors to fundamentally reassess their view of the economy. For 30 years or more, Britain has been seen as a welcome home for international capital, an English-speaking, business-friendly place for companies to base themselves inside the EU. Those advantages would have gone. There would not be an overnight exodus, but the supply of new investment would stop and existing businesses would reconsider their position. The economy would take a hit and that would in turn limit the ability of the Bank of England to support the pound with higher rates; so both sterling and the stockmarket might suffer. Investors are aware of some of this—a net 31% of those polled by Bank of America are underweight UK equities—but the nearer we got to March 2019 without a deal the more nervous they will become.

Source: economist

When the revolution eats itself