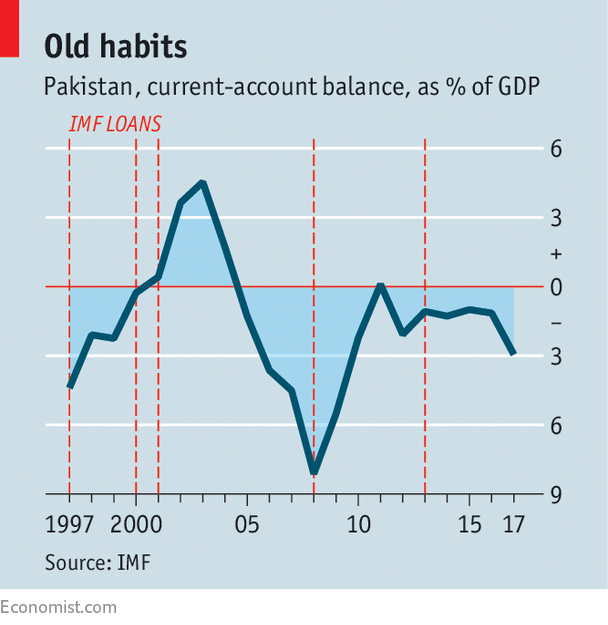

THE IMF, claims Pakistan’s government, is surplus to requirements. Ministers in its business-minded ruling party, the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N), boast of a record that means the country can pay its own bills. “We will not go back to the IMF programme,” declared Ishaq Dar, the finance minister, in May, almost a year after the completion of Pakistan’s most recent, $6.6bn bail-out. In a country that mistrusts Western assistance and where protesters portray the IMF as a bloodthirsty crocodile, such words have a heady appeal. But they ring hollow.

On June 16th the IMF warned of re-emerging “vulnerabilities” in Pakistan’s economy. It praised GDP growth of above 5% a year, but noted missed fiscal targets and a ballooning current-account deficit. The fund’s own projections a year ago for the fiscal year ending this June underestimated this deficit by about half the final total of $9bn. And based on trends in early April it overestimated the fiscal-year-end foreign-exchange reserves by $3bn.

-

How do you pronounce “GIF”?

-

The involuntary bumping of flyers is likely to be outlawed

-

An exhibition at the Design Museum in London shows colour in a new light

-

How whales started filtering food from the sea

-

Foreign reserves

-

Has “one country, two systems” been a success for Hong Kong?

Independent economists point out that, many times before, collapse has come on the heels of an IMF programme’s conclusion. Sakib Sherani, a former government economist, says that to avoid “egg on its face” for cheerleading Pakistan’s economic recovery just months ago, the IMF is slowly changing its story. By the end of 2018, many predict, Pakistan will come begging again. The fund responds that it is “too early to speculate”.

Some of Pakistan’s faltering can be blamed on bad luck, such as a fall in remittances from workers in the Middle East. But mostly it was, as usual, bad policy. Like its predecessors, the PML-N has failed to enact the structural reforms needed to break Pakistan free of its cycle of crises. Barely any goals of the IMF’s programme were met. Bloated, underperforming or, in the case of Pakistan Steel Mills, closed-down publicly-owned enterprises drain millions from the government each month. “Circular” debt, caused by delayed payments along the electricity-generation chain, is swamping the energy sector once more.

Annual exports have declined by 20% in dollar terms since 2013, stymied by an overvalued currency. All this means the government is again borrowing hand over fistfrom local and foreign banks. In some cases the design of the IMF programme itself has added to Pakistan’s woes: by pushing for increased tax revenue above all else, it has allowed the government to clobber the poor with indirect taxes, milk the (few) direct taxpayers even further, and, as ever, ignore the wealthy elites.

To make matters worse, instead of snapping its jaws at Pakistan’s failure to meet targets, the IMF meekly indulged its partner, argues Khurram Husain, a journalist working on a book about the relationship between Pakistan and the IMF. It kept acting “like an ATM machine”, he says, even as Pakistan kicked serious reform into the long grass.

The IMF has long been accused of going soft on Pakistan, mindful of its nuclear weapons, boisterous jihadis and proximity to war-torn Afghanistan. Successive Pakistani governments have exploited the sense that their country is too dangerous to fail. They have taken out 12 IMF loans since 1988. The result, argues Ehtisham Ahmad of the London School of Economics, is that aid money plays the role resource riches do in some other countries, encouraging spendthrift government.

The source of funds is changing even if government recklessness is not. China plans to invest $62bn in Pakistan for a range of projects, particularly power plants, around the 3,000km (1,875-mile) China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). That could lift Pakistan to more stable prosperity. But paying for the CPEC will not be easy. Unlike loans from the IMF or World Bank, some two-thirds of those taken out so far, for $28bn-worth of early projects, are on commercial terms, with interest high at around 7% a year. When these loans come due, argues Farooq Tirmizi, an emerging-markets analyst, Pakistan will need a bigger bail-out than ever before.

The IMF has concerns about the lack of transparency surrounding Pakistan’s CPEC debts and how it will repay them. Any future fund lending to the country may include conditions that sow discord between the country and its new patron. And with President Donald Trump in charge of America’s foreign policy, there is no guarantee that the old one, America, will prove as generous—in the event of a crisis—as it has in the past.

Source: economist

Pakistan’s old economic vulnerabilities persist