PUT the word Bitcoin into Google and you get (in Britain, at least) four adverts at the top of the list: “Trade Bitcoin with no fees”, “Fastest Way to Buy Bitcoin”, “Where to Buy Bitcoins” and “Looking to Invest in Bitcoins”. Travelling to work on the tube this week, your blogger saw an ad offering readers the chance to “Trade Cryptos with Confidence”. A lunchtime BBC news report visited a conference where the excitement about Bitcoins (and blockchain) was palpable).

All this indicates that Bitcoin has reached a new phase. The stockmarket has been trading at high valuations, based on the long-term average of profits, for some time. But there is nothing like the same excitement about shares as there was in the dotcom bubble of 1999-2000. That excitement has shifted to the world of cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum. A recent column focused on the rise of initial coin offerings, a way for companies to raise cash without the need for a formal stockmarket listing—investors get tokens (electronic coins) in businesses that have not issued a full prospectus. These tokens do not normally give equity rights. Remarkably, as many as 600 ICOs are planned or have been launched.

-

Rupi Kaur reinvents poetry for the social media generation

-

Green investors and right-wing sceptics clash on the meaning of scripture

-

The bitcoin bubble

-

The Phillips curve may be broken for good

-

Why hasn’t Bosnia and Herzegovina collapsed?

-

An act of terror in New York

This enthusiasm is both the result, and the cause, of the sharp rise in the Bitcoin chart in recent months. The latest spike was driven by the news that the Chicago Mercantile Exchange will trade futures in Bitcoin; a derivatives contract based on a notional currency. More people will trade in Bitcoin and that means more demand, and thus the price should go up. But what is the appeal of Bitcoin? There are really three strands; the limited nature of supply (new coins can only be created through complex calculations, and the total is limited to 21m); fears about the long-term value of fiat currencies in an era of quantitative easing; and the appeal of anonymity. The last factor makes Bitcoin appealing to criminals (although this is even more true of cash) creating this ingenious valuation method for the currency of around $570.

These three factors explain why there is some demand for Bitcoin but not the recent surge. The supply details have if anything deteriorated (rival cryptocurrencies are emerging); the criminal community hasn’t suddenly risen in size; and there is no sign of general inflation. A possible explanation is the belief that blockchain, the technology that underlines Bitcoin, will be used across the finance industry. But you can create blockchains without having anything to do with Bitcoin; the success of the two aren’t inextricably linked.

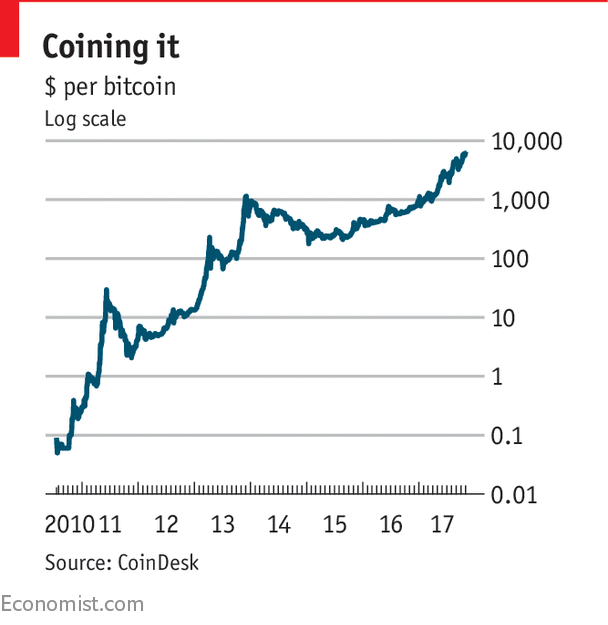

A much more plausible reason for the demand for Bitcoin is that the price is going up rapidly (see chart). As Charles Kindleberger, a historian of bubbles, wrote

There is nothing so disturbing to one’s wellbeing and judgment as to see a friend get rich

People are not buying Bitcoin because they intend to use it in their daily lives. Currencies need to have a steady price if they are to be a medium of exchange. Buyers do not want to exchange a token that might jump sharply in price the next day; sellers do not want to receive a token that might plunge in price. As Bluford Putnam and Erik Norland of CME wrote

Wouldn’t you have regretted paying 20 Bitcoins for a $40,000 car in June 2017 only to see the same 20 Bitcoins valued at nearly $100,000 by October of the same year?

Indeed, the chart is on a log scale to show some of the huge falls, as well as increases, that have occurred in Bitcoin’s history. As the old saying goes “Up like a rocket, down like a stick.”

People are buying Bitcoin because they expect other people to buy it from them at a higher price; the definition of the greater fool theory. Someone responded to me on Twitter by implying the fools were those who were not buying; everyone who did so had become a millionaire. But it is one thing to become a millionaire (the word was coined during the Mississippi bubble of the early 18th century) on paper, or in “bits”; it is another to be able to get into a bubble and out again with your wealth intact.

If everyone tried to realise their Bitcoin wealth for millions, the market would dry up and the price would crash; that is what happened with the Mississippi and the contemporaneous South Sea bubbles. And because investors know that could happen, there is every incentive to sell first. When the crash comes, and it cannot be too far away, it will be dramatic.

Source: economist

The bitcoin bubble