BOSCH is everywhere. It has 440 subsidiaries and employs 400,000 people in 60 countries. Its technology opens London’s Tower Bridge and closes packets of crisps and biscuits in factories from India to Mexico. Analysts call it a car-parts maker: it is the world’s largest, making everything from fuel-injection pumps to windscreen wipers. Consumers know it for white goods and power tools synonymous with “Made in Germany” solidity.

The company itself prefers to be called a “supplier of technology and services”, or “the IoT [internet-of-things] company”. On a hill overlooking Stuttgart, robotic lawnmowers whizz around its headquarters and a window displays dishwashers and blenders. Inside are signs of a company in transition: posters call on staff to rip off ties, celebrate “error-culture” and “just do it” opposite a quote from Robert Bosch, the founder: “Whatever is made in my name must be both first-class and faultless.”

-

Why London’s house prices are falling

-

Remembering Operation Torch on its 75th anniversary

-

What porn and listings sites can tell us about Britain’s gay population

-

How the taxman slows the spread of technology in Africa

-

“Alias Grace”, another triumphant Atwood adaptation

-

Retail sales, producer prices, wages and exchange rates

The 130-year-old giant’s attempts to become more like a tech company reflect a world where value comes increasingly from software, services and data, not things. When software and hardware meet, as they do in the field of autonomous cars or the IoT’s world of internet-connected objects, manufacturers risk becoming mere commodity suppliers. Part of Bosch’s answer is to position itself as a trusted custodian of data. “Orwell’s 1984 is kindergarten compared to the IoT-world. When it comes, and people re-evaluate privacy, Bosch will be prepared,” says Peter Schnaebele, its head of smart homes.

Soft power as well as hard

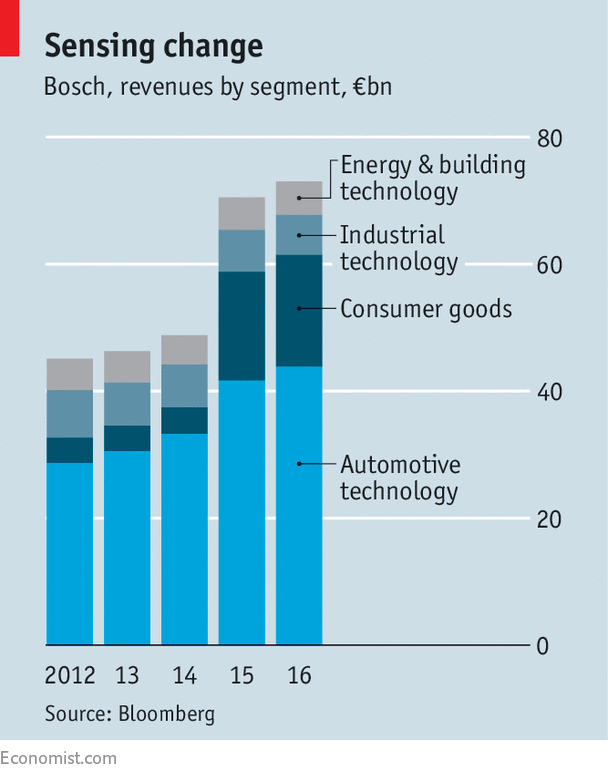

Bosch is 92%-owned by a foundation, freeing it to invest in long-term innovation. In 2016 it spent nearly a tenth of its revenue of €73bn ($85bn) on R&D. Recently it opened a glitzy research campus in Renningen. It also has a €420m venture fund and a startup incubator. In a converted warehouse in Ludwigsburg, north of Stuttgart, six teams of former employees work to turn more radical ideas into businesses.

Volkmar Denner, its CEO, says that he still sees Bosch’s future as a product company, but one that is heavily involved in software and “middleware” and that provides services on top. It has invested in software; built a platform (on which it runs IoT services and apps and allows other firms to do the same), called Bosch IoT suite; and last year launched its own cloud and data centre. That is unusual; two other industrial giants, General Electric and Siemens, use Amazon’s cloud to run their platforms. Bosch says it is seeking greater speed, flexibility and data security. It plans to open several more centres next year.

Bosch’s mantra is to increase the value of hardware with a “3S” strategy: sensors, software and services. Over half of its electrical-product classes are web-enabled; by 2020 all should be. Among its more telling bets is a €1bn investment in a semiconductor plant in Dresden for chips and sensors, to act as the “eyes and ears” of the IoT.

The long-term prize will be to use the data to teach things to think—by, for example, training the lawnmowers to respond to unexpected objects. The company last year started an artificial-intelligence (AI) centre, with 100 employees in Bangalore, Palo Alto and Renningen.

Because machines will be only as smart as the data they are fed, Bosch—which already “hosts” over 100,000 terabytes annually (1 terabyte fills 1,428 CD-Roms)—is gathering as much as it can. It crunches data from some British Gas customers to anticipate energy-maintenance needs, for example; data also pour in from factory floors and farmers’ fields filled with sensors. “Today we sell products and practically don’t have to care for them again because—being German-made—they’ll last,” says Christoph Peylo, Bosch’s head of AI. But in future products may need updating every two weeks, so “perhaps we’ll charge by volume of data, not hardware.”

Coup, an electric-scooter sharing scheme in Berlin and Paris (pictured), has no Bosch hardware at all. The company just provides the platform and buys the scooters in from Taiwan. It is Bosch’s first direct-to-consumer business in “mobility”. This area—loosely, anything that involves getting people from point A to point B—is crucial to Bosch, generating over half its revenue. The firm invests €400m per year in “electro-mobility”, or developing parts for electric cars, bikes, charging stations and so on. Some 3,000 developers work on driver-assistance systems. It holds nearly 1,000 patents for automated driving and by 2019 expects to make €2bn from driver assistance (double what it earned in 2016).

Sharing economy

Whether it is cars or the IoT, partnerships have become an efficient way to innovate. It was not always in the company’s culture to share with outsiders, says Lothar Baum, a data scientist at the firm. Indeed, Bosch is still seen by many as too conservative, cautious and cost-sensitive. But it is making connections with all sorts of other companies; from a map-building partnership with Apollo, a Chinese platform owned by Baidu, to working with Tesla on autonomous cars, to a deal with Amazon to use Alexa—its voice-controlled computer—to steer Bosch smart-home systems. “Especially in the pre-competitive stage, sharing makes sense,” says Mr Baum.

The big unknown is what will happen in the competitive stage. The race among leading IoT platforms is wide open. Eric Lamarre of McKinsey, a consultancy, divides the field into the horizontal tech platforms, such as Amazon; the more vertical manufacturers, such as Bosch and GE; and startup platforms. This is when questions around data become critical. Bosch thinks that customers will soon value data more than they do today. At the launch of the “Bosch IoT Cloud” Mr Denner noted that many companies and consumers say data-security concerns stop them using cloud technologies and connectivity products, offering its own cloud as an answer.

The firm hopes that manufacturing nous will still count for something, too. Even in a super-connected world “you don’t want to be surrounded by shoddy devices which are cheaply built,” says Mr Peylo. Last month Bosch’s smart security camera won the German Design Award; its white goods are selling like hot cakes in Asia. The company will continue to make non-shoddy products and to put its sensors into factories, homes and cars. It will almost certainly remain a big part of the “T” in IoT. The question is whether it can become far more than that.

Source: economist

A German hardware giant tries to become an ultra-secure tech platform