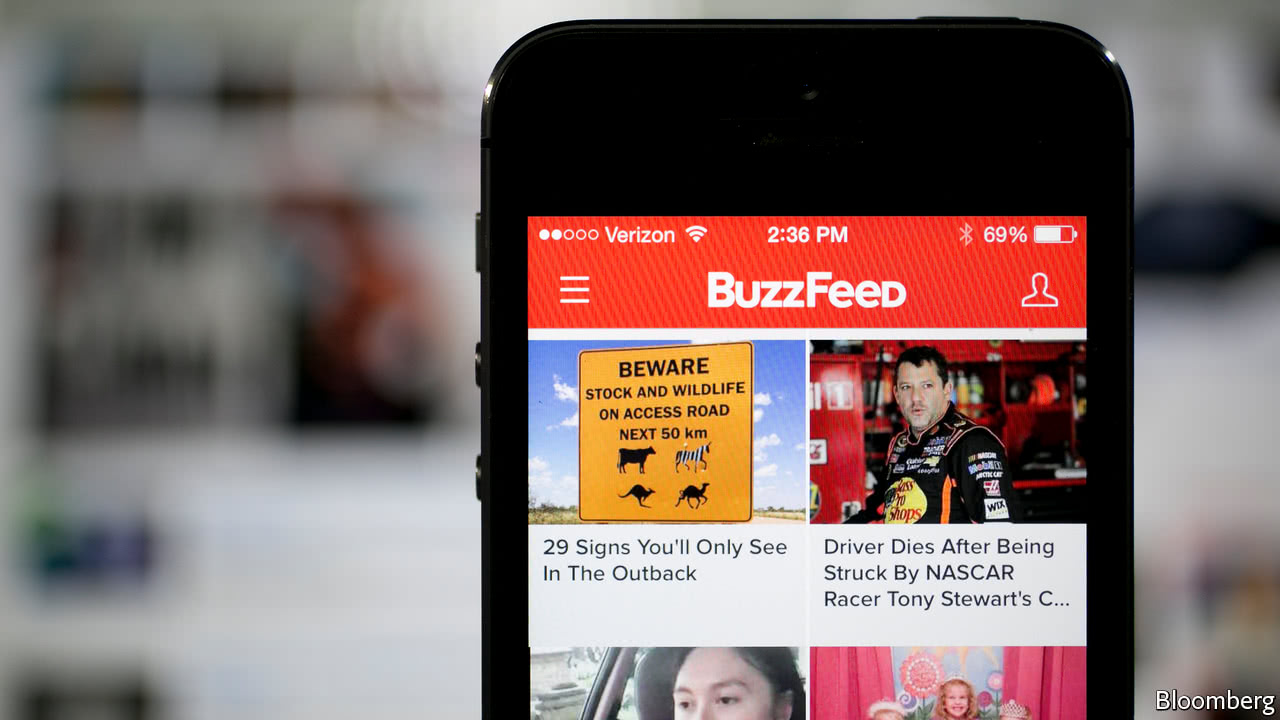

GREAT expectations attended digital journalism outfits. Firms such as BuzzFeed and Mashable were the hip kids destined to conquer the internet with their younger, advertiser-friendly audience, smart manipulation of social media and affinity for technology. They seemed able to generate massive web traffic and, with it, ad revenues. They saw the promise of video, predicting that advertising dollars spent on television would migrate online. Their investors, including Comcast, Disney and General Atlantic, an investment firm, saw the same, pouring hundreds of millions of dollars each into Vice Media, BuzzFeed and Vox (giving them valuations of $5.7bn, $1.7bn and over $1bn, respectively).

They have had successes. Some became ninjas in “SEO” long before most print journalists knew it stood for “search engine optimisation”. They introduced “clickbait” to the lexicon. Some, like BuzzFeed and Vice, worked out that fortunes were to be made in brand-supported viral hits—or “native advertising” that looks similar to the sites’ own snazzy editorial content. They gave the internet “listicles” like BuzzFeed’s “19 Mindblowing Historical Doppelgangers” (sponsored by Virgin Mobile) and uplifting stories, like those from Upworthy, where “you won’t believe what happened next”.

-

The music industry should be dreaming of a white Christmas

-

Australia is to hold a royal commission into the finance industry

-

The smashers of Mary’s images are acting more against statues than against her

-

American Airlines risks 15,000 flight cancellations after a rostering mishap

-

How to spot the next crisis

-

Foreign reserves

But a brutal winter is setting in. BuzzFeed will probably miss its revenue target, of $350m this year, by 15-20%, and is to lay off 100 of its 1,700 staff. Vice is also expected to fall short of its revenue target, of $800m. Mashable, a once-trendy site valued in 2016 at $250m, in November agreed to be sold for $50m to Ziff Davis, a print-turned-digital publisher. Other news sites are up for sale, cutting their staff or closing shop, sending ink-free scribes in search of work. Digital media are, in other words, enduring similar woes to their print peers. “There was this hype bubble that convinced everybody that these digitally native companies are different but they are not,” says an executive at one such previously overvalued firm. “People need to readjust their expectations.”

The natives have run into much the same problem as print newspapers have encountered: the duopoly of Alphabet (owner of Google and YouTube) and Facebook. The tech giants rule digital advertising in two ways. First, by dominating the business of selling and servicing ads, they take a healthy cut of those sold by publishers themselves. Second, they get advertisers to bypass publishers and spend directly on their platforms. Such is the demand that AdStage reckons ad prices on Facebook nearly tripled in only eight months this year, to $11.17 per 1,000 impressions. That is still a lot cheaper than native advertising—the bespoke ads made by firms such as BuzzFeed and Vice. Google’s and Facebook’s tools for targeting users strike advertisers as a more efficient, scalable way to reach specific audiences.

The duopoly are expected to get a majority of digital ad sales in America this year, and almost all of the growth. The media firms that supply Google and Facebook’s users with content are mere “vassals”, including digital news sites, says one executive. Digital publishers often act as such, attuning their strategies to the platforms in the chase for clicks. After Facebook prioritised video content last year, so many sites made a “pivot to video” that it became an industry joke. It has not worked out well, as short videos are difficult to make and monetise at volume.

Publishers would be wiser to get users to stay on their own sites, so that they can profit from the relationship. Some are trying to do so with their journalism. Gizmodo Media Group, a group of tech and culture sites, has an investigative team. Vox makes in-depth explainer videos on current events. BuzzFeed regularly breaks big stories. The site holds its audience: the “bounce rate” of BuzzFeed’s visitors—the share that leave after visiting one page—is 34%, which compares pretty well with 54% for the New York Times (the numbers come from SimilarWeb, an analytics firm).

Advertising still provides the bulk of revenue. But publishers are also selling things to visitors, both their own merchandise and other companies’ products, on which they take a cut. The Gizmodo sites (owned by Univision) get about one-quarter of their revenue from e-commerce; BuzzFeed has started doing the same. Membership fees may be another option.

Smaller digital operations are also using a variety of strategies. The Ringer, a sports and culture site in Los Angeles, has established a niche in podcasts, on which it generates millions in sponsorship. The Information, in San Francisco, has more than 10,000 subscribers paying $399 a year for its technology news. At VTDigger, a non-profit site started by a laid-off journalist, dogged coverage of politics and corruption in Vermont has attracted strong readership and a mix of donations, grants and sponsorships from local businesses. There are several clear paths to long-term survival, but not to billion-dollar valuations. Expectations have indeed been readjusted.

Source: economist

Digital news outlets are in for a reckoning