“WHAT does not kill me makes me stronger,” wrote Nietzsche in “Götzen-Dämmerung”, or “Twilight of the Idols”. Alternatively, it leaves the body dangerously weakened, as did the illnesses that plagued the German philosopher all his life. The euro area survived a hellish decade, and is now enjoying an unlikely boom. The OECD, a club of mostly rich countries, reckons that the euro zone will have grown faster in 2017 than America, Britain or Japan. But, sadly, although the currency bloc has undoubtedly proven more resilient than many economists expected, it is only a little better equipped to survive its next recession than it was the previous one.

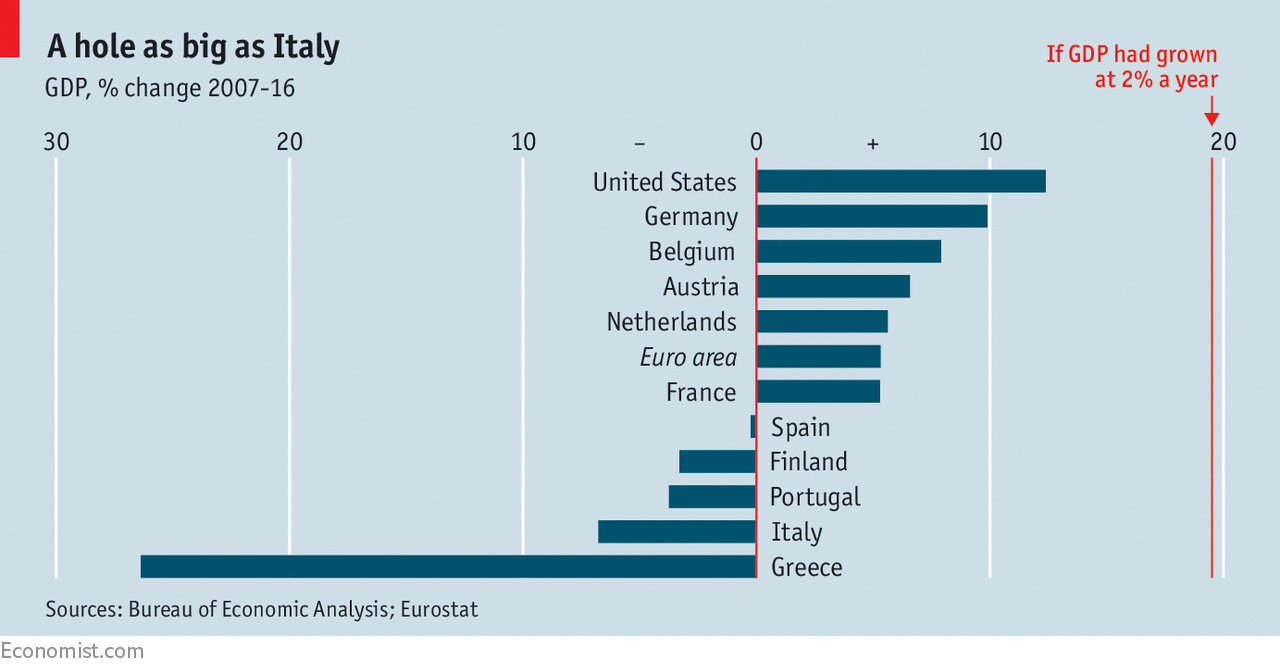

Europe’s crisis was brutal. Euro-area GDP is roughly €1.4trn ($1.7trn)—an Italy, give or take—below the level it would have reached had it grown at 2% per year since 2007. Parts of the periphery have yet to regain the output levels they enjoyed a decade ago (see chart). The damage was exacerbated by deep flaws within Europe’s monetary union. Three shortcomings loomed particularly large. First, the union centralised money-creation but left national governments responsible for their own fiscal solvency. So markets came to understand that governments could no longer bail themselves out by printing money to pay off creditors. The risk of default made markets panic in response to bad news, pushing up government borrowing costs and adding to financial strains. In 2012 the European Central Bank (ECB) stepped in, declaring that to keep control of its monetary policy it was willing, as a last resort, to buy government bonds. Panic subsided, bond yields dropped and the most acute phase of the crisis ended.

-

The music industry should be dreaming of a white Christmas

-

Australia is to hold a royal commission into the finance industry

-

The smashers of Mary’s images are acting more against statues than against her

-

American Airlines risks 15,000 flight cancellations after a rostering mishap

-

How to spot the next crisis

-

Foreign reserves

But the euro-area economy continued to languish in or near recession through 2014 because of the second flaw. During serious economic downturns, central banks usually cut interest rates to encourage new borrowing and investing, and governments swing into action by running larger budget deficits to make up for falls in private spending. When the financial crisis first hit, the ECB, like other rich-world central banks, cut its rates to near zero; governments cut taxes and spent freely. Yet the euro area was to face unique difficulties. The ECB was constrained by its mandate—a 2% inflation ceiling (as opposed to the 2% target common elsewhere)—and the influence of the inflation-averse German Bundesbank. Not until deflation threatened could the ECB begin stimulative asset purchases, long after other central banks.

Governments were unable to compensate for this monetary-policy inertia. The ECB’s promise to buy government bonds threatened to liberate euro-area economies from the discipline imposed by markets. European leaders, and Germany in particular, sought to enforce sobriety through other means. The emergency-lending programmes negotiated with the most beleaguered economies exacted hefty budget cuts as the price. All members were bound by a “fiscal compact” that euro-zone leaders signed up to in 2012. It urged member states to keep deficits within set limits, balance budgets over the long run, and adopt plans to reduce government debt to no more than 60% of GDP. Adherence has been incomplete, but the short-term impact was that public borrowing fell sharply across the euro area between 2012 and 2016, prolonging the pain of the crisis.

European leaders still argue over how to meet the currency zone’s macroeconomic needs. Emmanuel Macron, the French president, favours reforms that would allow for a euro-area budget large enough to cushion the economy against shocks, and a finance minister to oversee it. Realistically, such mechanisms are years away from agreement, let alone implementation.

Euro-Dämmerung

Happily, Europe’s recovery did not wait for such reforms, but that makes them no less essential. The euro-area rebound, in its early years, relied on exports. Crisis and austerity gutted domestic spending, and led to wage-depressing levels of unemployment. So troubled euro-area economies began selling much more abroad than they were buying; foreign consumers, in effect, threw the desperate periphery a lifeline. Strong global growth still helps European exporters, but other factors add to economic momentum. The severest budget-cutting is over. And falling unemployment is buoying consumer spending—particularly in Germany, where the boom has been longest and strongest.

Growth works wonders. A bigger tax take makes deficit-reduction easier; hiring and consumer spending feed on each other. So long as moderate oil prices and strong global growth continue, Europe’s economic health will improve. Unfortunately, such tailwinds cannot last forever. The third and gravest threat to the long-run survival of the euro area endures: the mismatch between the scope of its economic institutions and its political ones.

No European institution enjoys the democratic legitimacy of a national government. Crisis drove European institutional reform in areas such as bank supervision, but also concentrated power in unelected institutions like the ECB—even though the fiscal compact was negotiated by heads of government. Without new political institutions (which, in fairness, he also wants in the form of a euro-zone parliament), Mr Macron’s euro-area budget and finance ministry would seem like more of the same.

The euro area is in a political bind. Among the legacies of its crisis are nationalist parties across the continent, rooted in anger at pain seemingly inflicted by unaccountable European politicians. Any move towards greater European integration lends credence to their warnings of lost sovereignty. But failure to agree on such measures raises the odds that the next downturn will be a bad one, which would also play into nationalists’ hands.

A decade of pain cost Europe its ability to sell integration as a force for prosperity. If it does not use its current good fortune to remodel itself, the interlude will come to be seen in retrospect not as a moment of triumph, but as a last, missed opportunity to build a euro zone that can survive.

Source: economist

The euro zone’s boom masks problems that will return to haunt it