It’s the time of year, and that moment in a bull market, when investors start wondering whether to lock in some gains or let them ride.

I know firsthand of one financial advisor email saying, “Your portfolio is up nicely this year and the market’s appreciation has made the asset allocation look pretty aggressive. Want to lighten up on equities?” And no doubt, this is one such note among thousands.

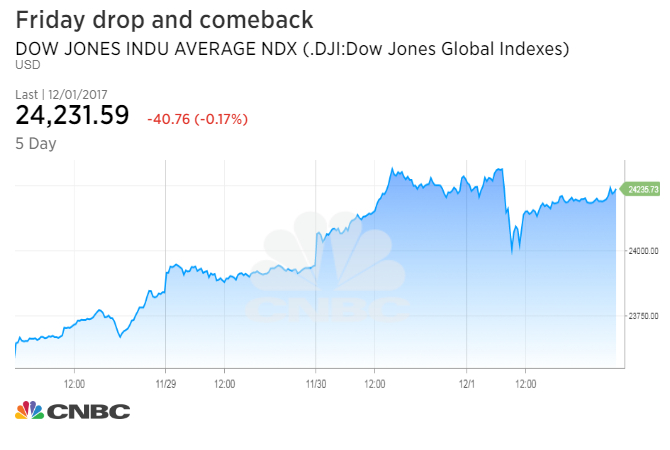

Meantime, professional managers who earn a cut of annual performance have incentive to trim market risk in December to preserve their take and sidestep any “tape bomb” — such as the brief air pocket on Mueller investigation headlines on Friday.

One trading-advisory service for institutions I follow has been spot-on bullish all year but counseled clients to “go flat” last Thursday — because technical targets set early this year were met and “this is the first time [in 2017] that sentiment is just too extended” as enthusiasm grew for year-end upside capped by a corporate tax cut.

This strategist also expects significantly more upside by the end of 2018, after what would amount to the biggest market shakeout since mid-2016.

So where does that leave the typical investor?

The weight of the evidence continues to suggest that no important market peak is nearby — the market almost always becomes more unstable before a major top is forming.

Yet logic and the basic rhythms of the market also tell you that less-generous market conditions should be expected to take hold before too long.

Bespoke Investment Group tidily sums up how munificent this market has been: “The S&P 500 is in its second longest bull market, the tenth longest streak without a 10 percent correction, the fourth longest run without a 5 percent decline, and the longest rally without even a 3 percent decline on record.”

Not all calms give way immediately to storms. Bespoke looked at the 10 years when the U.S. stock market most behaved like it has in 2017 through the first 11 months. In those years, December was positive 80 percent of the time, with average and median returns a bit better than the usual.

In the year following those “most similar years,” I calculated the average return was a 7.5 percent gain, with eight of 10 years positive, four years up more than 20 percent, two substantial declines.

And another fun tidbit: In the S&P 500’s 90 years of existence, December has never been the worst month of any year. If this holds, December would be better than the worst month so far in 2017 — in March, when it slipped just 0.04 percent.

All the same, another slug of stats says we’re due for a bit of a pause or setback before too long. The S&P 500 was up eight-straight months through November. Since 1980, such a streak has only reached nine months once, in 1983, according to Urban Carmel of the Fat Pitch blog.

Short-term trader sentiment measures also seem over-bullish and suggest further upside could be minimal before a bit of choppiness. As for retail-investor positioning, the American Association of Individual Investors’ asset-allocation poll shows members’ exposure to stocks are as heavy as it was near the 2000 peak.

Yet all the tendencies of this market — extreme calm, long upside streaks, healthy market breadth, positive responses to upbeat economic data — also indicate that the first, say, 3 or 7 percent setback, whenever it comes, won’t be the “big one.”

Bull markets usually weaken and get sloppy before they end altogether. Unlike in romance, when it comes to stocks, the first cut is rarely the deepest.

Stocks did well most of this year largely ignoring Washington and treating the chance of a tax-cut package as a potential bonus rather than a crucial driver of stocks. (After all, the MSCI Emerging Markets and Nasdaq 100 ETFs are up around 30 percent in the past year, and neither is a direct beneficiary of lower tax rates on U.S. businesses.)

But lately, traders have been programmed to react to headlines that bear on the likelihood, size and timing of corporate tax cuts. Maybe a more interesting question than “How much of the tax-cut news is already priced in?” (Some, probably not all.) is “How will the tax cuts be priced in?” (Unevenly, and perhaps not enduringly.)

There’s some evidence that lower tax rates will catalyze another round of dramatic rotation within the market rather than an “all boats lifted” response. Domestic-oriented sectors and those with high tax rates are already outperforming global, low-tax groups.

Beneficiaries will most likely be companies that will quickly take shareholder-friendly action with the added after-tax profit and repatriated overseas cash.

Deutsche Bank strategist Binky Chadha says a 20 percent corporate rate would boost his 2018 S&P 500 profit forecast by 12 percent. But he expects the index price-to-earnings multiple would come down because the market would not extrapolate a one-time benefit such as a tax cut into future years.

Equities tend to look through one-time events, and most research on corporate tax cuts says they are “competed away” over time.

Add this to the facts that the bond and currency markets are not acting as if lower taxes will cause a sudden acceleration in U.S. growth and we’re already near full employment and into a Fed tightening cycle as we cut taxes, and the trade becomes more complicated.

This doesn’t mean a tax cut would likely be a good “sell on the news” event. And while stocks don’t owe investors much at this point, bull markets tend to give the faithful more than they deserve before demanding payback.

But the tax stimulus at all-time highs complicates the picture for a market that is now feasting on perceived good news in a way it hadn’t for years — and is growing expensive and perhaps complacent as it goes.

Source: Investment Cnbc

Investors' December dilemma: Take profits or ride the rally