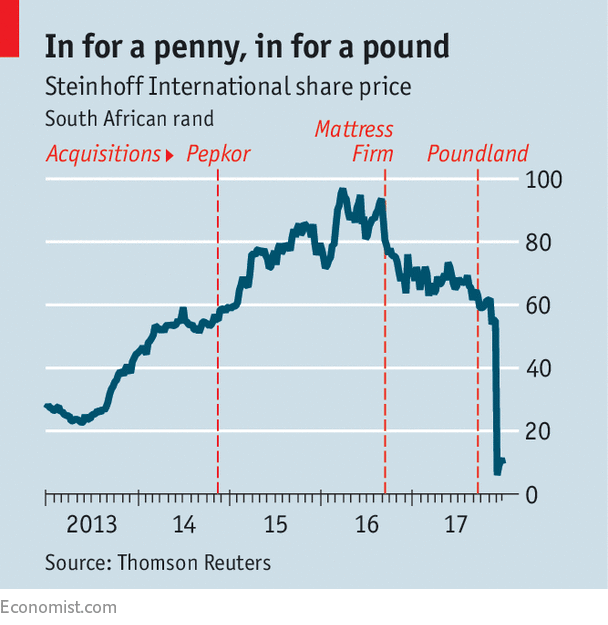

THE scale is staggering, even by the standards of scandal-worn South Africa. Steinhoff, a retailer that is one of the country’s best-known companies, admitted to “accounting irregularities” on December 6th when it was due to publish year-end financial statements. Its chief executive, Markus Jooste, resigned, and the firm announced an internal investigation by PwC. Within days Steinhoff had lost €10.7bn ($12.7bn) in market value as its share price fell by more than 80% (see chart). Much is unclear, but it is shaping up to be the biggest corporate scandal that South Africa has ever seen. The company has said it is reviewing the “validity and recoverability” of €6bn in non-South African assets.

Steinhoff traces its roots to West Germany, where it found a niche sourcing cheap furniture from the communist-ruled east. The company merged with a South African firm in 1998 and is based in Stellenbosch, near Cape Town—a Winelands town that is home to some of the wealthiest Afrikaner businessmen. It recently pursued a debt-fuelled expansion, buying furniture and homeware chains, from Conforama in France and Mattress Firm in America to Poundland in Britain, becoming Europe’s second-largest furniture retailer after IKEA. It has 130,000 employees at 12,000 outlets in over 30 countries.

-

Retail sales, producer prices, wages and exchange rates

-

Foreign reserves

-

“The Last Jedi” tears down—and rebuilds—the Star Wars franchise

-

Why Turkey and Greece cannot reconcile

-

When politicians and executives get caught out

-

Lessons from ancient Greek coinage

Between June 2014 and September 2016 Steinhoff expanded its assets by 145% as its acquisition spree intensified. This splurge added to its financial complexity and might have helped it to hide bad news. A recent report by Viceroy Research, which hunts for stocks to sell short, or bet against, accuses Steinhoff of using off-balance-sheet vehicles to inflate profits and mask losses. Viceroy’s analysts concluded that these vehicles were controlled by associates and former executives of Steinhoff, and that they engaged in transactions with Steinhoff that the firm failed to disclose.

They also allege that Steinhoff made loans to these entities, allowing it to book interest revenue that was never likely to be translated into cash. This, they argue, went hand in hand with “round-tripping”, in which large blocks of business were moved off the books and only the profitable bits were then brought back on. The firm has not commented in detail on the analysis, though it has denied impropriety.

Steinhoff’s biggest shareholder is Christo Wiese, one of South Africa’s richest men. One money manager wonders how Mr Wiese could have been unaware of accounting problems. But there are also questions over the level of due diligence performed by some large financial firms. Steinhoff was a top-15 stock by market value on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE); many fund managers had it in their portfolio. Investec, a bank, has warned that it could lose up to 3% of its annual post-tax profit, from trading in Steinhoff-linked derivatives. Deloitte, Steinhoff’s auditor, is also under scrutiny over the scandal, although the audit regulatory body has said it may not have been in the wrong.

The biggest damage could be suffered by South African pensioners. The Government Employees Pension Fund (GEPF), with more than 1m members, is one of Steinhoff’s biggest shareholders, with a stake of around 10%. The GEPF said its stake in Steinhoff amounted to 1% of total assets, making the collapse in the share price “significant but manageable”.

The South African parliament’s public-accounts committee is less phlegmatic: it has called for Steinhoff to be investigated by an elite police unit called the Hawks. The JSE and South Africa’s corporate and financial regulators have all said they will investigate whether Steinhoff breached regulations. German investigators, meanwhile, have been looking at the company’s accounting practices since shortly before its listing in Frankfurt in December 2015.

Steinhoff’s share price has recovered slightly, but is expected to be volatile until more is known about the firm’s liquidity position and the nature of the accounting “irregularities”. Steinhoff has appointed Moelis & Company, an investment bank, to advise on talks with lenders, and AlixPartners, a consultancy, to help with “liquidity management and operational measures”. An annual meeting with lenders in London has been postponed to December 19th. “We’re all in the dark,” says David Shapiro of Sasfin Securities. “Speculating whether there is value or not—there’s no point, it’s too early.”

Source: economist

An accounting scandal sends Steinhoff plummeting