THE collapses of Enron and WorldCom in the early years of this century turned book-cooking into front-page news. Investors lost over $200bn; in 2002 the stockmarket fell by over a fifth between April and July. In response, America’s Sarbanes-Oxley Act set up a new body, the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB), to supervise auditors.

Its quest to give auditors more teeth continues, with the introduction of new rules that James Doty, its outgoing chairman, bills as the most significant changes to reporting by auditors in over 70 years. The question now is whether Mr Doty’s successor, who was announced by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) on December 12th along with four new PCAOB board members, will keep heading in the same direction.

-

What is it about “Cat Person”?

-

Retail sales, producer prices, wages and exchange rates

-

Foreign reserves

-

“The Last Jedi” tears down—and rebuilds—the Star Wars franchise

-

Why Turkey and Greece cannot reconcile

-

When politicians and executives get caught out

New disclosures on auditors’ tenure and independence take effect this week. And from 2019 auditors must go above and beyond the low bar they have historically set themselves, which is a pass or fail “opinion” on whether financial statements obey accounting rules. They will have to explain “critical audit matters”, meaning occasions when they had to confront company management. Many big firms loathe these changes, warning that investors will be swamped by minutiae. Their real fear may be a loss of control over the flow of information to investors.

The rules are meant to mitigate the incentive problems that have long riddled the profession, which is dominated by the Big Four partnerships—Deloitte, EY, KPMG and PwC. To foster investor trust, listed firms must engage external auditors. But companies pay them, not investors, which may dampen the motivation to scrutinise.

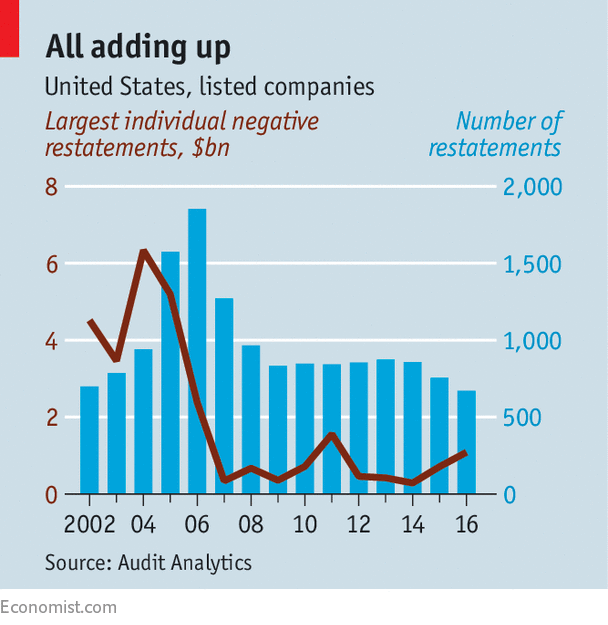

In the West, stronger oversight does appear to have coincided with better quality. Accounting scandals are far from consigned to history’s ash heap. In America last year, for example, PwC settled a $5.5bn lawsuit alleging negligence when it gave Colonial Bank a clean bill of health in the years before the lender’s collapse in 2009; the bank turned out to have made loans against assets that did not even exist. Yet both the frequency and the severity of accounting restatements have fallen over time in America (see chart), and inspectors are finding fewer audit deficiencies. In Britain, where auditors have been required to discuss contentious bits of the audit for some years already, 81% of FTSE 350 audits inspected by regulators in 2016 either met their standards or had only minor problems, up from 56% five years before.

But two big weaknesses in the audit industry remain. First, at a global level, quality is still relatively low. A survey of 36 countries last year by the International Forum of Independent Audit Regulators found that an “unacceptably high” 42% of 855 audits did not meet inspectors’ standards. All of the Big Four have been caught up in scandals in recent years, particularly in emerging markets.

American regulators can lift standards. The PCAOB inspects audits for all firms listed in America, regardless of the auditor’s location (though China refuses its inspectors access). More of its sanctions have been taken against foreign firms, including affiliates of the Big Four. In its severest punishment ever, it fined Deloitte in Brazil $8m last year for doctoring paperwork and hiding evidence from inspectors.

Senior executives at the Big Four admit to embarrassment about violations abroad. But because most country firms are legally distinct affiliates, they have been able to avoid broad reputational damage. And the worry is that neither companies nor regulators can afford to discipline auditors harshly for their failings because of the second big flaw: limited competition. The Big Four dominate audit for large listed companies, scrutinising the accounts of 99% of those on the S&P 500 and the FTSE 100. Companies’ choices are even more limited because conflict-of-interest rules forbid the same firms from selling consulting and audit services. Over 85% of S&P 500 companies have been audited by the same firm for over ten years, according to Audit Analytics, a data provider. Such cosiness jeopardises objectivity.

How this should be addressed, if at all, is unclear. Mr Doty reckons independence of auditors must be the priority; if that is assured, a lack of competition, in itself, is less worrisome. In any case, the PCAOB has little scope to act, since the House of Representatives voted in 2013 to ban mandatory auditor rotation. In contrast, European regulators now require firms that have used the same auditor for ten years to put their contract out to tender. Nevertheless, the four remain dominant.

That concentration worries some. What happens if another scandal were to sink one of the firms, turning the Big Four into the Titanic Three? European regulators are now monitoring risks to audit firms; in Britain, audit-firm boards must include independent non-executive directors. Steven Harris, an outgoing PCAOB board member who helped to draft Sarbanes-Oxley, would like to see similar rules in America.

That seems unlikely, because of a new risk to audit quality: a possible relaxation of American policy. Many bosses hope for looser rules. That would fit with the Trump administration’s deregulation agenda. Although Sarbanes-Oxley has not ranked highly on the list of rule books to be burned, Mr Doty’s successor, William Duhnke, a former Republican Senate aide, is thought to favour deregulation. Two of the four other new board members are former Big Four auditors. Reassuringly, the SEC’s chair, Jay Clayton, has said he is not looking for radical change. He would be wise to consider how much progress has been made since the dark days of Enron and WorldCom before consigning audit regulation to the flames.

Source: economist

America’s Public Company Accounting Oversight Board gets a new boss