WHEN Donald Trump became America’s president nearly a year ago, lobbyists campaigning for protection for the country’s airlines against competition from the Middle East were overjoyed. But they were less happy on December 13th when it was revealed that Donald Trump has decided to hold off on imposing sanctions against the three big Gulf carriers—Emirates of Dubai, Etihad of Abu Dhabi, and Qatar Airways—for what America’s big airlines allege are unfair subsidies that they receive from their governments. For now, the administration will continue discussions with the UAE and Qatar, the trio’s home countries. But it has not taken off the table the possibility in the future of amending or terminating its Open Skies agreements that allow the Gulf carriers to fly to any American airport they want. A document from an administration meeting in September, obtained by Politico, a news website, states that “additional steps” may be taken “if sufficient progress is not made by a date certain”—probably a few months from now.

-

Donald Trump holds off hitting the Gulf carriers with sanctions

-

What may happen to the internet in America

-

What is it about “Cat Person”?

-

Disney’s purchase of Fox’s entertainment assets is a gamble on media’s future

-

Retail sales, producer prices, wages and exchange rates

-

Foreign reserves

The three big American legacy carriers—American, Delta and United—are campaigning hard for the American government to take action. Delta, for instance, accuses Emirates of receiving $9.5bn in state aid between 2004 and 2015, $17bn for Etihad and a whopping $25.5bn for Qatar. The Gulf carriers deny that they have received any subsidies, but the American trio see the Trump administration’s protectionist leanings as their chance to push their agenda through.

Earlier this month they were nearly successful. A senator from Georgia (home to Delta) inserted a provision into the tax bill currently going through Congress that would force the Gulf airlines, as well as some others, to pay American corporate taxes. Currently, airlines generally pay taxes in their own countries, regardless of whether their revenue comes from there or overseas, and the proposal would have crimped the Gulf carriers by forcing them to pay more tax. Unsurprisingly, opposition to the proposal was fierce. Etihad called the proposal “inappropriate under US law and contrary to several international agreements.” And the International Air Transport Association, an industry group which represents the interests of legacy carriers around the world, objected to the measure’s reversal of “decades of precedent—which the US has long supported—on the taxation of international aviation.” The provision was ultimately dropped from the tax bill because the Office of the Parliamentarian, which enforces Senate rules, deemed it extraneous to the main content of the bill.

Still, it provides some insight into the type of retaliatory action the Trump administration could take against the Gulf carriers. Even though such a move might give American airlines a temporary competitive boost, it would clearly be bad for flyers, who are much better served by fair competition on price and service. As this newspaper has previously explained, a lack of competition in American aviation has resulted in higher fares and poorer service than airlines provide in Europe. And the American airline industry is already far from fully competitive market:

Instead of using its carriers’ complaints as justification for more protection, America would do more for its citizens by ending its restrictions on foreign ownership of airlines and offering complete freedom to operate internal flights. American consumers would gain regardless of whether governments, in the Gulf and elsewhere, reciprocated.

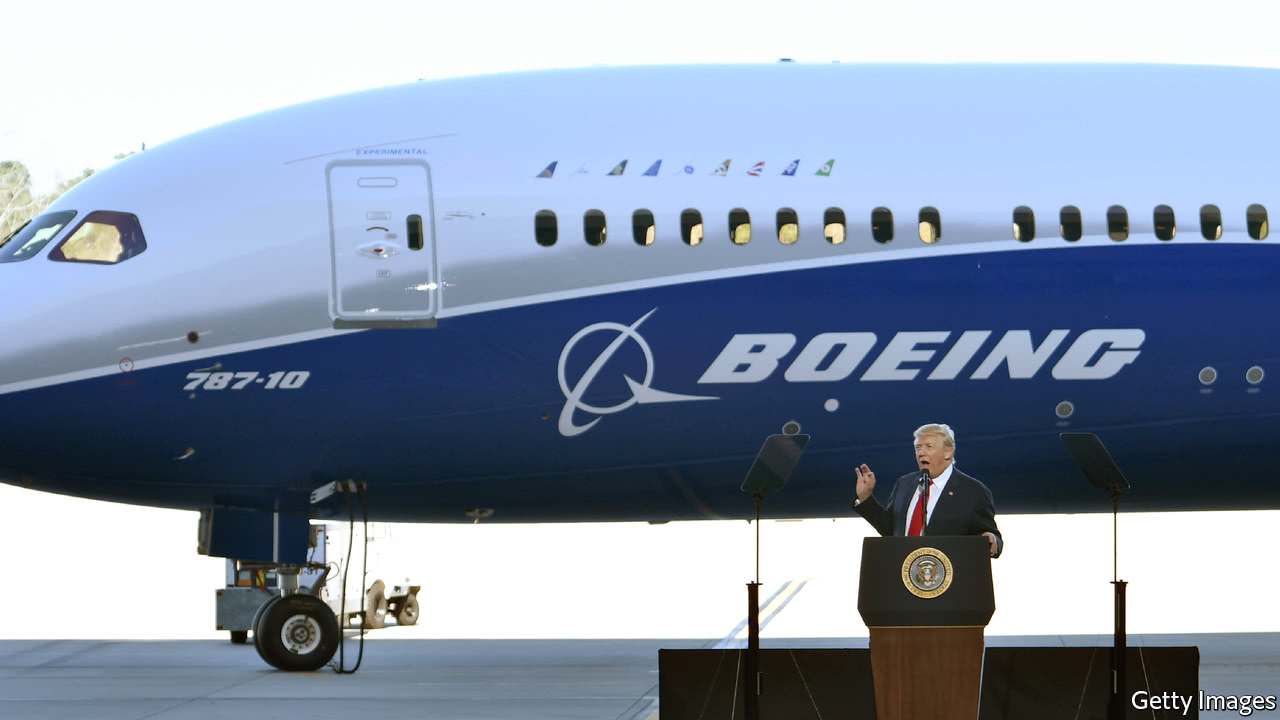

Penalising the Gulf carriers would also hurt the American economy. Boeing, a planemaker which is America’s largest exporter, is heavily reliant on the three carriers as customers. Etihad has 48 Boeing planes in its fleet, Qatar has 91, and Emirates has 147 Boeing 777s in its fleet, with a further 196 on order. If a trade war over flying rights were to prompt these carriers to cancel any future orders from Boeing, the impact on American manufacturing workers and the country’s broader economy is likely to be far greater than any small benefit that workers at Delta and American and United would derive from Mr Trump tilting the playing field in their employers’ favour.

And there is more than a little hypocrisy in American airlines’ complaints about government support for the Gulf carriers. A report by the Congressional Research Service in 1999 found that since 1918, the American government had propped up the country’s airlines with $155bn in direct and indirect subsidies—and the number has only gone up in the nearly two decades since. There are plenty of good reasons why the Gulf “super-connectors” are snapping up a growing share of the international aviation business. Their location makes flying via the Gulf a convenient place for a layover on flights between Asia and Europe and the Americas. Their investment in new planes, good service, and marketing has also forced their competitors to improve their offerings. Ordinary Americans could enjoy lower fares and better service too—if only the Trump administration leaves America’s skies open to competition.

Source: economist

Donald Trump holds off hitting the Gulf carriers with sanctions