JEFF BEZOS does not like sitting still. In his annual letter to Amazon’s shareholders this year, he warned of “stasis. Followed by irrelevance. Followed by excruciating, painful decline. Followed by death.” Competitors are toiling to avoid the same fate but it is hard to keep up. On June 16th Amazon said it would pay $13.7bn for Whole Foods, an upscale grocer known for its organic produce. Lest be accused of sloth, four days later Amazon announced a new service to let shoppers try clothes at home, for no fee, then return those they don’t like.

The news that Amazon would make clothes shopping even easier is a blow to America’s apparel chains, many of which are already in the middle of that excruciating decline. Yet it was the Whole Foods deal, more than ten times bigger than any acquisition Amazon has made so far, that caused the bigger stir.

-

Retail sales, producer prices, wages and exchange rates

-

Foreign reserves

-

How the euro zone deals with failing banks

-

The Supreme Court says offensive trademarks are protected speech

-

The hope for Democrats after special-election losses

-

Disappointment for the Democrats in a fiercely fought congressional race

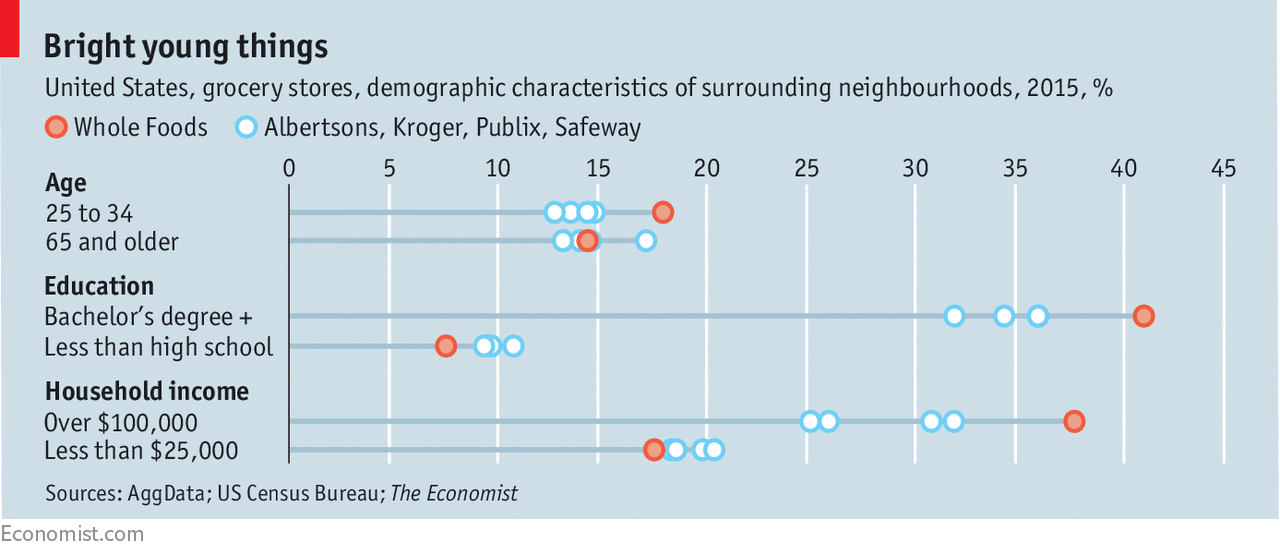

The deal’s precise impact is hard to gauge. Buying Whole Foods hardly gives Amazon a stranglehold on food and drink: the combined companies will account for just 1.4% of America’s grocery market, according to GlobalData, a research firm. The people who shop at the chain are not the mass market. They are unusually wealthy and well-educated (see chart). Mr Bezos has made no big announcements about changes at Whole Foods—drone-delivered spelt grain is unlikely to become a reality soon. Instead he simply praised its work and said “we want that to continue.”

Nevertheless, the news prompted the shares of a large group of rival grocery firms, including Walmart and Kroger, to sink quickly. As with so much about Amazon, the Whole Foods deal is important not for what it represents now but how it might transform Amazon and up-end rivals—most notably, Walmart—in future.

Up to now, grocery has been a tough nut for Amazon to crack. A growing share of office supplies and clothes are bought online, yet last year e-commerce accounted for just 2% of American spending on food and drinks. Amazon Fresh, a ten-year-old grocery-delivery service, is still in only 20-odd cities. Prime Now, a two-hour delivery service introduced in 2014, is in 31.

That is because grocery’s margins are low and its goods devilishly hard to deliver. Peaches bruise. Meat rots. Many consumers like to buy food in person: unlike choosing a battery or book, selecting a ripe tomato requires inspecting it or trusting someone who has.

Amazon has tried to solve these problems—using machine learning, for example, to distinguish ripe strawberries from mouldy ones. But the Whole Foods deal is the start of something new. To date Amazon has run only a handful of stores; Whole Foods will give it more than 450. Amazon knows a lot about customer behaviour online; now it will be able to marry that to data about habits in physical stores. Paul Beswick of Oliver Wyman, a consultancy, notes that Whole Foods will provide a well-established supply chain, a boon to Amazon Fresh, as well as a roster of store-brand goods, which might now be sold online.

It is all a huge headache for Walmart. The beast of Bentonville remains the world’s largest store and America’s biggest grocer, with revenues of $486bn compared with Amazon’s $136bn. It too is trying to avoid stasis. It paid $3bn last year to acquire Jet.com, a challenger to Amazon, and has invested in technology to help customers order groceries online and have them ready to pick up from its stores. Walmart is experimenting with other services: some staff deliver groceries on their way home.

“Walmart is testing, reading and reacting,” notes Oliver Chen of Cowen, a financial-services firm. “That’s a new Walmart.” On the same day that Amazon said it would buy Whole Foods, Walmart announced the purchase of a menswear brand called Bonobos for $310m, which began online and now has three dozen stores. The deal, among other things, gives Walmart new staff to help the company transform itself further.

Yet Amazon is playing a different, more complex game. It is enmeshing itself in its customers’ lives: each new service, from streaming video to its Alexa virtual assistant, makes it more integral to a person’s day. That gives it new data and revenue that help it improve services and offer additional ones. Shoppers buy groceries often. If Amazon can become part of Americans’ ritual of buying milk and eggs, the firm will understand its customers even better. Shoppers will have fewer reasons to go elsewhere.

And Amazon is likely to integrate Whole Foods in ways that are not yet obvious. Finding ways to get more value out of its investments has been key to Amazon’s growth. The company’s warehouses, built for its own goods, are now used by independent sellers. The same is true of its cloud-computing power, which supports not just Amazon’s own business but legions of other firms. Amazon may use its infrastructure for Prime Now to deliver Whole Foods’ groceries. In future it may develop new services for Whole Foods that are in turn deployed in new ways, suggests Ben Thompson, a tech blogger. It could, for example, supply restaurants.

For Walmart, and many other rivals, the best scenario would be if regulators were to slow Amazon’s expansion. The company accounts for about half of new spending online in America. It has reached into many parts of the economy, from retail to cloud computing and from entertainment to advertising. Yet intervention is improbable. The Whole Foods deal gives Amazon less than one-fiftieth of the grocery market. Walmart, were it to make Whole Foods a higher offer, by contrast, would be very likely to attract regulators’ wrath. In such circumstances, Walmart could be forgiven a severe attack of sour grapes.

Source: economist

Amazon’s big, fresh deal