WHEN it comes to inflation, the Federal Reserve sometimes resembles a child freshly emerged from an age-inappropriate horror film. To its members, runaway price increases seem to lurk in every oddly shaped shadow. On June 14th America’s central bank raised its benchmark interest rate for the third time in six months, even as inflation lingered below its 2% target, as it has for most of the past five years. Some critics reckon the Fed’s 2% inflation target is too constraining. Indeed, in recent comments on a letter from prominent economists calling for a higher target, Janet Yellen, the chairman, signalled openness to the idea. But the Fed’s problem is less its target than an unforgiving pessimism about American productivity. If its bleak view is wrong, the Fed itself is partly to blame for slow growth.

Economists generally treat productivity growth as a “real” factor, outside central-bank control. Thus, it is thought to depend on things such as technological progress, workers’ skill levels and the flexibility of the economy. But productivity growth is cyclical: it varies depending on whether an economy is booming or busting. Central banks might therefore have more influence over it than they are prepared to admit.

-

A new front in the legal fight over Donald Trump’s travel ban

-

Qatar Airways wants a 10% stake in American Airlines

-

Ireland and Afghanistan become the first new Test nations in 17 years

-

Ireland and Afghanistan become the first new Test nations in 17 years

-

Why calculating a British parliamentary majority is so tricky

-

Humanist nuptials are popular in Scotland but only beginning in Ulster

Economies have a growth speed limit, determined by changes in population and productivity. When unemployment is high, the economy can grow faster than this speed limit without an acceleration in inflation, since firms can expand by hiring unemployed workers. As the number of jobless workers shrinks, this option disappears. Eventually, firms hoping to grow must raise wages to poach the workers they need from other companies. As wage costs rise, prices must go up to cover the bill, fuelling a cycle of accelerating inflation. “The risk would be that the economy would crash to a very, very low unemployment rate,” said William Dudley, president of the New York Fed, on June 19th, describing a scenario most Americans may find less than horrifying.

Yet before that point firms have other ways to manage increased demand. They might give their current workers more hours, or push them to work harder. Some have the option to outsource work to foreign contractors or invest in robots. Even rising wages need not translate into higher inflation. Firms may choose lower profits over higher prices and reduced market share. They might also pair wage increases with investment in training and equipment in order to raise workers’ productivity. In an economy in which the central bank permits inflation to jump around, it should be clear when these other opportunities are exhausted: when inflation begins to rise sharply. So long as inflation remains low and stable, it is possible that productivity-boosting steps are still being left on the table.

Could this be happening now? Some evidence suggests so. Until the mid-1980s productivity grew faster when a boom gathered pace; it slowed in recessions. Since then, the opposite has been true; productivity growth leaps in recessions and wheezes during booms. Structural changes in the economy may help account for this change. Increased labour-market flexibility might make it easier for firms to sack workers in bad times, boosting average productivity; they can rehire low-skilled workers later. But other factors probably matter at least as much, according to work published last year by John Fernald, of the San Francisco Fed, and Christina Wang, of the Boston Fed. In particular, technology may be contributing to economic fluctuations in a new way.

Routine procedures

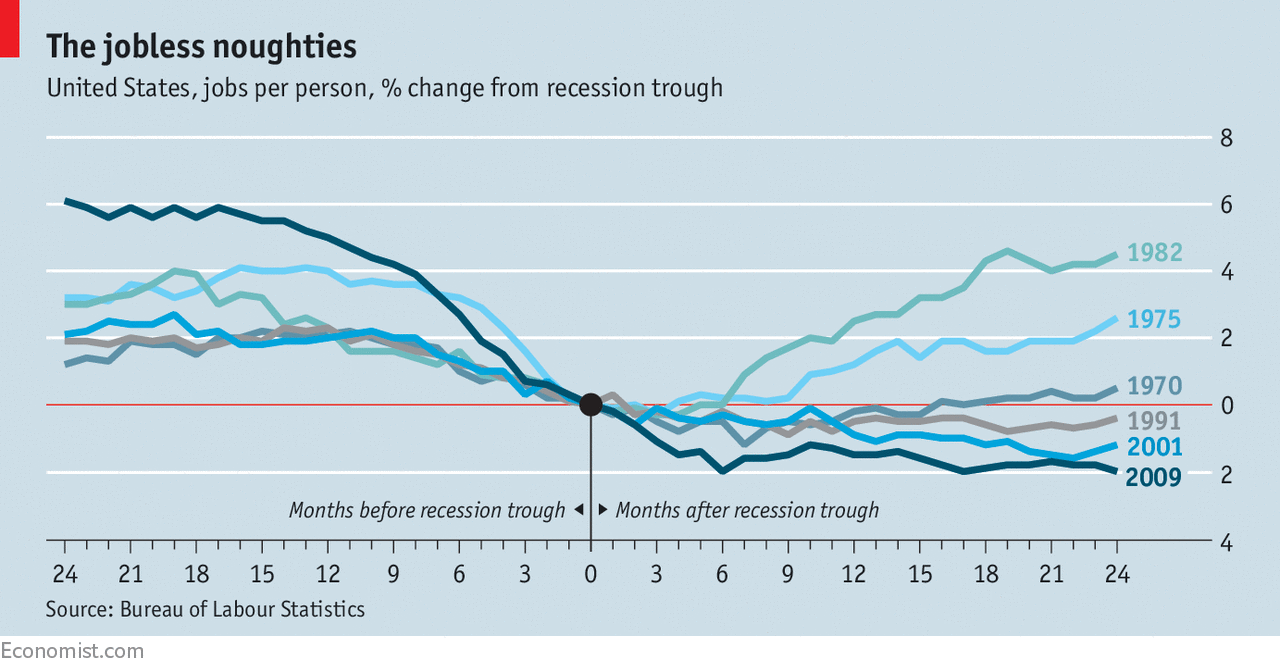

Around the time productivity began to leap during recessions, America also began suffering a rash of jobless recoveries (see chart). In a paper published in 2015, Nir Jaimovich, of the University of Zurich, and Henry Siu, of the University of British Columbia, argue that this is because firms began responding to recessions by eliminating routine jobs (like repetitive factory or call-centre work) through reorganisation, outsourcing and automation. Firms used recessions to implement labour-saving structural changes that raised productivity and made it easier to accommodate rising demand in the early stages of a recovery without hiring new workers.

The shift to a low-inflation world can help to explain this phenomenon. Firms tend not to cut their workers’ nominal wages (the numbers on the pay cheque), and when inflation is low they cannot achieve such large savings by keeping pay constant in the face of rising prices. They therefore have little choice but to make lay-offs—and to take additional steps to make the remaining, expensive workers more productive.

What is more, technological progress itself is contractionary if the central bank does not recognise it is occurring, according to a seminal paper, published in 2006, by Susanto Basu, of Boston College, Mr Fernald and Miles Kimball, of the University of Colorado. New technologies generally reduce labour demand and inflation in the short run. That would not be so if central banks observed that this was happening and responded with more accommodative policy. They rarely do.

The rare exception makes the point. In March 1997 the American economy seemed to be running at close to full tilt. Inflation was just a shade over 2%. The unemployment rate stood at 5.2%. In the eyes of the Fed, then run by Alan Greenspan, it was very nearly time to pull away the punchbowl. Yet, though the Fed voted for a 0.25% interest-rate increase at that meeting, its plan for a series of rate rises was subsequently ditched when it changed its collective mind. Unemployment eventually fell below 4%; since the early 1980s no other period has matched the late 1990s for growth in labour productivity and real pay.

The only way to know if America can manage a repeat performance is to test the economy’s limits. The transition from a 2% target to a higher one would offer a chance for such an experiment. As it is, a central bank hell-bent on keeping inflation low and stable risks cutting short a boom with room to run.

Source: economist

The Federal Reserve risks truncating a recovery with room to run