NINE straight highs for the Dow Jones Industrial Average might suggest that all is well with capitalism. But on the contrary, they could be a sign that things have been going profoundly wrong with the way the system is working.

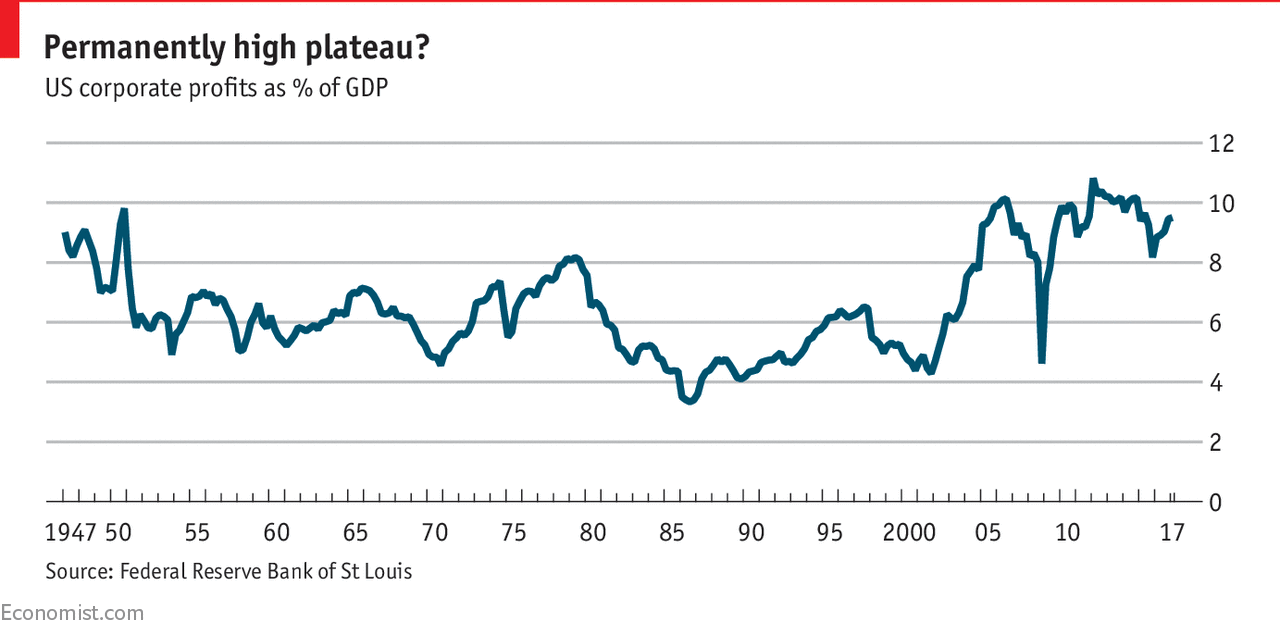

The main driver for the surge in share prices this year has been the strength of profits; second quarter profits for S&P 500 companies are around 12.6% higher than a year ago, according to Andrew Lapthorne at SG, a French bank. As the chart shows, relative to GDP, profits seem to be regaining their levels of recent years. And those levels are much higher than they have been in much of the post-war era (see chart).

-

Why an eight-hour bus ride from Los Angeles to San Francisco might beat a flight

-

Pricey London property may push Labour voters into Conservative constituencies

-

A legal defeat for a pious prison gardener is good news for bosses

-

Capitalism and the absence of creative disruption

-

“Icarus” reveals the mastermind behind Russia’s doping programme

-

A Google employee inflames a debate about sexism and free speech

Jim McCaughan of Principal Global Investors says he is not too concerned about this since the nature of capital has changed; no longer is the economy dominated by manufacturing where businesses have to invest in heavy equipment, blast furnaces and the like. But that argument, which has been knocking around since the dotcom boom, strikes me as unsatisfactory. In essence, the argument boils down to the return on capital having risen. But if that is the case then entrepreneurs round the world should be piling in, creating new businesses and expanding existing firms – especially in the light of low interest rates. The resulting competition should drive profits back down.

That clearly isn’t happening, suggesting something about capitalism has changed. One reason could be that certain sectors are now in the hands of effective monopolies, particularly in technology where network effects favour incumbents (see our coverage of this issue). Creative destruction may not be happening any more. And that may explain why economic growth and productivity improvements have been sluggish in recent years.

It is possible, of course, although three big caveats are needed. There have been several cases in the last 20 years when companies have thought they had an enduring advantage (AOL, Nokia and Blackberry, for example), only for events to overtake them. Secondly, big business was dominated by monopolies in the early 20th century, only for populism to strike back in the form of trust-busting measures. The same could happen today; barely a day goes by without a tech company facing public controversy. Third, the marginal cost of many tech products tends towards zero which suggests that price competition eventually ought to bite hard. The tech giants may yet be cut down to size.

When it comes to the stockmarket, Jeremy Grantham of GMO has a new note pointing out that investors tend to award high valuations to shares when, like now, profit margins are high and inflation is low and stable. But if one believes that margins are mean-reverting, this shouldn’t happen. When profits are high, investors should fear that they will fall and pay a low multiple of current profits; instead valuations have only been higher in 1929 and the late 1990s.

Mr Grantham thinks that any shift to lower valuations would have to be accompanied by a sustained fall in margins or a rise in inflation (or both). And neither is going to happen soon. He may be right on both counts. But that should worry those who are hoping for a return to healthy economic growth. And all “this time is different” arguments should remind us of when Irving Fisher said, in 1929, that stocks had reached a “permanently high plateau”.

Source: economist

Capitalism and the absence of creative disruption